Heavy-hearted mockingbird

Videos by American Songwriter

Never sang; was never heard

Waiting for the perfect word

She lost her will to fly

So hush now, don’t be blue

If you were me and I were you

We’d still not know what to do

But I’d be coming by

From “Horses in Blue” By JD Souther

He’s the only guy in history who could have been an Eagle but didn’t want to. As he said at the time, “The Eagles will be just fine without me.”

David Geffen, who signed the band, disagreed. “But you’re still going to write with them, right?” he asked. “Of course,” JD Souther answered, shaping the dream life— he could write hits with the Eagles but didn’t have to go out on tour. Instead, he could stay home and write songs for himself and with his girlfriend, Linda Ronstadt.

“Tough choice,” he said dryly.

Souther went on to become one of the great pop collaborators of all time. With Don Henley and Glenn Frey, he wrote many of the Eagles’ biggest hits (including “Best of My Love,” “Heartache Tonight,” and “New Kid in Town;” also “How Long,” which he wrote by himself). Souther also wrote many songs that Linda Ronstadt recorded, including great duets such as “Hearts Against the Wind.” With his pal James Taylor, he co-wrote and dueted on their beautiful hit, “Her Town Too.” Other great singers, such as Jackson Browne and Bonnie Raitt, recorded his songs.

He also wrote classics for himself, including his biggest and own iconic standard, “Only The Lonely.” But he contained multitudes then, as he still does, unknown to many of his fans. His genius for writing songs was not restricted to country-rock. Though raised mostly in Amarillo, Texas, it was never country music that lit his fire. Nor was it rock, folk, or blues. It was jazz. Although he accidentally became one of the world’s most successful and beloved songwriters, his dream was to play drums behind a killer jazz band.

You can talk about it but the love still grows

If wishes were horses in blue

I’d be trampled in your dreams

What could I do? I’m still in love

I’m so in love with you

Regardless of genre, to Souther, it was always the melody that meant the most. His grandmother, an opera singer, introduced him to many of the world’s most timeless melodies. “Nessun dorma,” Giacomo Puccini’s famously dramatic aria from the opera Turandot, was the first song he ever learned to sing. Not exactly kid’s stuff.

His father, a big band singer, raised him on a healthy diet of timeless standards, forever shaping his tuneful soul with a “complete saturation” in the songs of Cole Porter, George Gershwin, Johnny Mercer, and the other legendary songwriters of standards.

Though he liked and played rock ‘n’ roll, it never supplanted his first love: timelessly melodic standards. Always he yearned for a return to the fabled age of melody. But rather than wait for a new epoch to begin, he got to work. By 2015 he’d composed some of his greatest songs, all richly melodic like those songs of yore. They became Tenderness.

It wasn’t easy to do, but he persisted. “You’ve gone to the well so many times,” he said, “that it gets harder and harder to draw something out of it. The water level keeps dropping a little bit. So you go deeper.”

Deeper. Instead of staying in the shallows, he took Miles Davis’ advice to heart: “Play something you don’t know.”

Produced by Larry Klein, Tenderness was cut with Souther’s dream band of genius jazz players, with arrangements by the great Billy Childs. With their support, he discovered that place in a song that so many decry is unreachable in modern times. It’s the intersection of poignantly poetic human stories imbued with a musical spirit that lifts the song far beyond words into a timeless realm. These are songs from the deep soul of a tender-hearted, sophisticated romantic, the very kind of songs people complain nobody writes anymore. Tenderness is one of the most beautifully poignant song cycles to emerge in decades, and couldn’t have come at a better time. It’s there where our conversation began.

AMERICAN SONGWRITER: ‘Tenderness’ is a masterpiece— congratulations. Such amazing writing. “Horses In Blue,” especially, is just stunning.

JD SOUTHER: Thank you! That is quite an abstract work. In this day and age, it is heartwarming to hear melodies like these.

I couldn’t have done it without Larry Klein. He is wonderful. He flew out here [to Nashville] a couple of times. He mostly sat on my living room floor, shuffled lyric pages around, and listened. We talked about what might work well with it. He’s a very, very perceptive musician.

Also, he agrees with my theory about music, the thing I live by, which is that you should never be comfortable. You should always try something new and play something you haven’t ever tried before. I think if you’re serious about it, you can get better as you get older. Miles said, “You have to play a long time, man, to be able to play like yourself.”

AS: Does that apply to songwriting, too?

JD: For me it does. I think if you’re just going to keep playing something over and over, being comfortable fouls up a lot of musicians. You never want to be too comfortable.

Joni [Mitchell] said something about that years ago. When she was being criticized for changing her music so much. She said, “If I didn’t, I would be criticized for that, for staying the same. And If I change it, I get criticized for changing. So I do what makes me happy.”

AS: That is a challenge for all songwriters/artists, don’t you think? The industry never encourages you to do something different. And if you do and it doesn’t sell well, it discourages others from trying it.

JD: It’s hard. Very often those albums don’t sell, too. That album of Laura Nyro songs that Billy [Childs] got a Grammy for, nearly broke the bank at Sony Masterworks. It’s one of the reasons Tenderness didn’t do very well. Because they kept making things that didn’t sell, but which were wonderful.

AS: This is why writing these songs is heroic. It takes a certain kind of courage to do this now, despite the industry discouraging it.

JD: Well, the music is going to be there anyway. Whether the audience loves it or not. The thing to judge in anybody is what you project when you have ideas, and if you feel fulfilled at the end of the day. You still might wake up in the morning and want to do something different. ‘Cause it comes in waves. You don’t play every day. You don’t write every day. But you probably should. You know what they say about inspiration always striking when the pencil is in your hand? It’s probably true. If you’re busy writing all the time, one of these days, you’re going to get something good.

You have to embrace the mistakes, too. That’s another thing Miles said. “There are no wrong notes. It’s the note you play after that note which determines whether it was wrong or not.” What you play after can make it right.

AS: Did you write these songs on piano? Or can you write melodies like these on the guitar?

JD: You can get that melody out of an empty room! But, yeah, some of them are on the guitar. I can play all those grown-up jazz chords on an acoustic guitar.

I thought of the album as a soundtrack. It was like I was making a movie I couldn’t afford to shoot. So I just did the soundtrack.

AS: You’re unique in being someone who can write great songs alone, and a famously beloved collaborator.

JD: To me, the biggest advantage of writing with somebody else is that it gets finished sooner. You’re always pushing each other to do it a little bit better. And there’s also a little implied criticism going back and forth. You want to push the other person to the best thing they’ve got. Because your name is going to be on it too.

So I think it’s one of the reasons why Henley and Frey and I wrote together as well as we could. And we were friends, and also really complete believers in the spirit of collaboration. Almost brothers. But we were very competitive with each other. Intensely so. Almost nasty.

Generally, we decided that flattery was going to get us absolutely nowhere.

Let me put it this way: Here are sort of the three levels of response: The first one is that if it wasn’t good, nobody said anything. Just dead silence.

If you said something that was pretty damn good, but not the greatest, one of us would say, “I think we can fit it in.”

And if something was really good, Glenn would say, “Those kids are gonna love it.” And we were 23 at the time. Calling an audience “kids” was pretty presumptuous. Glenn was the great critic—he would give a peace sign with both hands.

AS: Would all three of you equally contribute?

JD: For the most part. Glenn had the best rock & roll sensibility; Henley had the best blues sensibility; I had the best jazz sensibility. Don and I are both inveterate readers. We never stop reading. And Glenn is just one of the most rhythmic human beings I have ever met. He is midwestern rock ‘n’ roll.

AS: Why didn’t you join the Eagles?

JD: Because I am a terrible team player. Geffen wanted me in the band. We actually rehearsed a set and played it for him. I remember looking down the stage thinking, “Man, this is an awful lot of singers and acoustic guitar players all in the same band. I felt, “I’m not necessary here.” And I don’t really like being told what to do in any sense anyway.

AS: Did you make the right decision? Did you ever regret it?

JD: No.

AS: Did writing great songs always come easy to you?

JD: No. It never came easy. There are no rules in songwriting, except to write a great song. People know the famous ones mostly. But between those were hundreds which weren’t good.

[Songwriting] is more of a journey, really, than a job. You have to delve into the unknown. you go through phases of writing complex songs, and then you turn around and search for simplicity. It’s an adventure, but it’s real. It’s an adventure of real heart and soul, and when it really resonates with other people, that is the ultimate. That is the dream. And dreams, you know, they sometimes do come true.

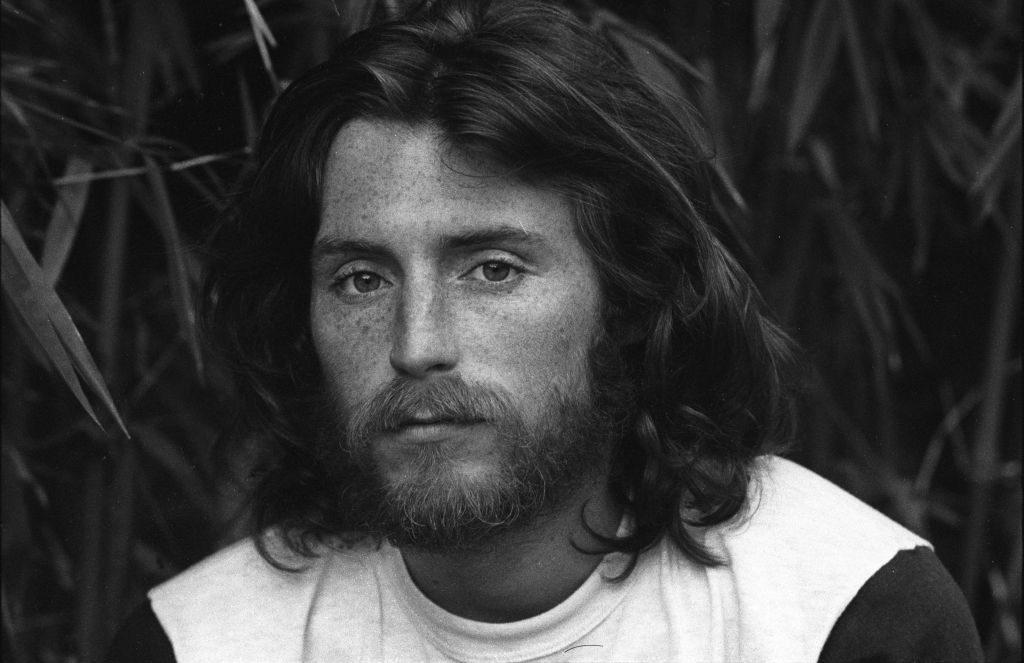

Main Photo by Jeremy Cowart