Videos by American Songwriter

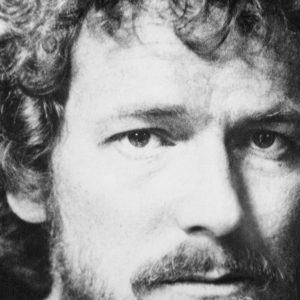

Composer and multi-instrumentalist Ornette Coleman is, at 77, a revered musical figure-the winner of both a 1994 MacArthur Genius award and a Pulitzer Prize this past spring. His 2005 concert disc Sound Grammar made history by becoming the first recording to win the coveted prize.

Composer and multi-instrumentalist Ornette Coleman is, at 77, a revered musical figure-the winner of both a 1994 MacArthur Genius award and a Pulitzer Prize this past spring. His 2005 concert disc Sound Grammar made history by becoming the first recording to win the coveted prize. (It was not even among the 140 music nominees.) A remarkable date (“date” is jazz term for LP) that features Coleman on alto sax, violin and trumpet accompanied by his son Denardo on drums and bassists Gregory Cohen and Tony Falanga, it marked his return to recording after an absence of almost a decade. It blended both new originals and reconfigurations of classic tunes like “Turnaround,” “Matador” and “Waiting for You” from such previous Coleman dates as Tomorrow Is The Question, Sound Museum and Colors. It also reaffirmed his distinctive approach to composition, melody, harmony and rhythm, something that’s set him apart from his peers since his startling early albums for Lester Koenig’s Contemporary Records label in the late ‘50s.

Composer and multi-instrumentalist Ornette Coleman is, at 77, a revered musical figure-the winner of both a 1994 MacArthur Genius award and a Pulitzer Prize this past spring. His 2005 concert disc Sound Grammar made history by becoming the first recording to win the coveted prize. (It was not even among the 140 music nominees.) A remarkable date (“date” is jazz term for LP) that features Coleman on alto sax, violin and trumpet accompanied by his son Denardo on drums and bassists Gregory Cohen and Tony Falanga, it marked his return to recording after an absence of almost a decade. It blended both new originals and reconfigurations of classic tunes like “Turnaround,” “Matador” and “Waiting for You” from such previous Coleman dates as Tomorrow Is The Question, Sound Museum and Colors. It also reaffirmed his distinctive approach to composition, melody, harmony and rhythm, something that’s set him apart from his peers since his startling early albums for Lester Koenig’s Contemporary Records label in the late ‘50s.

Although he got his start playing in R&B and blues bands around his native Fort Worth, Texas, Ornette Coleman’s sound and style alternately thrilled and scandalized jazz fans, musicians and critics when his early recordings (The Music of Ornette Coleman: Something Else and Tomorrow Is The Question) were released. Both Coleman and his cornet/trumpet-playing companion Don Cherry played in an angular, slashing manner, doing songs that weren’t locked into the conventional structural patterns usually associated with jazz. Detractors felt Coleman and Cherry didn’t-or couldn’t-swing, and that Coleman’s arrangements and tunes were more noise than coherent music. Yet close listening to these recordings reveal he was clearly influenced, even at that time, by Charlie Parker (someone he frequently praises and credits today with getting him interested in playing music). Though he doesn’t emulate Parker’s tone, nor move as smoothly or easily through the passages, you can often hear Parker’s impact in his octave leaps, sensibility and mood.

After Coleman and Cherry attended the Lenox School of Jazz in Massachusetts in 1959 at the behest of pianist/composer John Lewis (a longtime Coleman champion), they had a series of engagements at the Five Spot club in New York and were subsequently signed to Atlantic Records. During the ‘60s, Coleman’s recordings for Atlantic-and some others for Blue Note-cemented his reputation and more clearly defined his concepts, though it didn’t quell the criticism from some quarters. Perhaps the most famous album was the 1960 date Free Jazz, a 37-minute collective improvisation. But other releases like The Shape of Jazz to Come, Change of the Century and Jazz Abstractions further expanded his concept, while latter, longer works with symphonic connections (Forms and Sounds for Wind Quintet) showed he was also keen on the classical sound. Most importantly, Coleman continued moving away from the 32-bar, AABA song pattern. His works were concerned first and foremost with sound; songs could be lengthy or short, totally improvised or fully structured, and have extensive solo sections or periods with numbers featuring unison playing.

Coleman’s music took another turn during the ‘70s, following a 1972 visit to Morocco. While his own playing became more animated and bluesy, he began incorporating aspects of funk and rock into his material. The formation of a new band, Prime Time, in 1975, which contained two electric guitarists, an electric bassist and drummer, cemented that change. And by the ‘80s, Coleman’s music was even looser, more celebratory and intense, though it still emphasized freedom and expressiveness. Among his landmark ‘80s dates was Song X, a duo recording with Pat Metheny that brought him an expanded fan base and renewed critical appreciation. Now, even longtime detractors have taken a fresh look at Coleman’s music. Some acknowledged that there had always been plenty of blues and even bop influence, though he’d frequently ignored conventional time passages in his works.

Unfortunately, Coleman’s music has also been widely (and probably accurately) viewed as noncommercial throughout his career. Though he’s done many recordings for a number of labels, since the late ‘90s, he only made a couple of dates prior to Sound Grammar. One was a 1997 session with Rolf Kuhn for the Intuition label, and another was an amazing set titled Joe Henry for Mammoth in 2000. This 10-song set includes pieces such as “Richard Pryor Addresses A Tearful,” “Rough and Tumble,” “Cold Enough to Cross” and “Scar,” and pairs Coleman with a large group and orchestra whose ranks include pianist Brad Mehldau, bassist Me’Shell NdegeOcello, drummer Brian Blade and Sandra Park serving as concertmaster. It’s as freewheeling, explosive and fluid as any vintage Coleman recording, and showed that, at 70, he was still capable of exciting, frenzied solos on alto.

Ornette Coleman remains enthusiastic about music and is willing to answer any and all questions about any subject. He downplays any notion that he’s an innovator, and insists that everything goes back to the basics: sound, rhythm, harmony and melody.

Who were the people that initially interested you in playing and writing music?

Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk are the two people who I think are the most important, because, when you listen to their music, you hear such feeling in what they’re doing. Emotion has always been far more interesting to me than technique, because no matter what people may say, we’re all working with the same notes and the same scales. It’s what you do with those notes that count. I can show you on a transcription sheet how a piece of music looks, and you can read it…but that doesn’t really say anything. It’s the attitude that you bring to that music, the way you play those notes and the things that you do with them that’s important. There’s a social quality in music, and a relationship between music and society that’s always been important. When you take Parker or Monk, and you hear the way they used their music in relationship to others, that’s the important thing to me. The music that people like to call jazz is much more about feeling than about formality, though you certainly have to know and respect the music in order to play it successfully.

Why do you think there were such strong negative reactions towards your music in the beginning? Did people misunderstand what you were doing, or did they just not want to consider it because they felt you were too radical or outside the music mainstream?

I always had an idea in mind in terms of music, and it was my idea to write and play something that was more spiritual than physical. I knew the structure; that doesn’t take anything special. If you have the key of C on a piano, then-if you have even a little musical training, you know what will happen if you go in either direction. The same is true for the treble or bass clef, so anyone who plays an instrument knows the language of music. What’s more important to me is taking that language and then shaping it to say something positive and instructive…that’s the spiritual side of music. Sometimes that involves taking a note that some think should be sharp and, instead, making it flat or playing it natural. If you hear it in an unusual, or what some might think is an unusual structure, then you might say that doesn’t sound right. I think that’s what the people who didn’t like what I was doing in the beginning were doing. They were listening to my music with their expectations that it was supposed to sound a certain way based on their interpretation of music. But I’ve studied music all my life, and I know all the conventional things you’re supposed to do in writing songs. It wasn’t so much that I wasn’t interested in doing that, although I guess I wasn’t, but that I wanted to write and play music that I felt would speak to people in a different way. That’s still what I’m interested in doing today.”

You have developed the “harmolodic” concept, which, as best someone who’s a longtime lapsed pianist can understand, represents an evolution of what you did with free music. How do you explain to those who don’t play music exactly what ‘harmolodic” means?

Look at it this way. You take the basic notes and instead of approaching them in a restrictive manner and saying that you can’t take that step if you play this note, start thinking about sound and what you can do with sound. That’s really all I’m doing with harmolodic-thinking differently about melody, rhythm and harmony. It’s more based on listening and responding, on sound and reaction, than any type of set pattern I could write out for you. Music has nothing to do with a lot of the things that people like to think it does. It has nothing to do with race, for example. It does have something to do with culture, background and environment, but the style of bebop and the people who played it…anyone with an open mind and heart can also play that music. They won’t play it the way Charlie Parker played it, but they bring their own experiences to it. So to get back to your question, I’m really writing music that doesn’t necessarily adhere to the conventional or the expected, but does have its own system and language. It’s just one based more on sound and freedom than anything else.

You’ve played in all sorts of configurations with many of the greats in, not only jazz, but also classical and world music. Who are some of your favorite musicians in terms of working relationships?

I’ve been blessed to play with many extraordinary people, but there are three people that I would name as…perhaps those I’ve really enjoyed playing with more than any others. Ed Blackwell was incredible, an incredible drummer. He seemed to sense immediately what I wanted to do whenever we played together. It was so amazing how he could anticipate rhythmically what direction I wanted to go in any situation. Charlie Haden is a phenomenal bassist, someone who’s always inspiring in his playing, and always gives you far more than you can expect and everything that you need. Don Cherry was a great friend and a wonderful player, someone whose ideas and personality were always a great spark and comfort. I miss all those guys [Cherry and Blackwell are deceased, Haden’s still active]. The music that we made together was really the essence of freedom.

Congratulations on winning the Pulitzer Prize. Do you feel that’s kind of a validation for what you’ve done throughout your career?

To be perfectly honest, while I’m humbled and very appreciative of the award and every other honor I’ve received, that’s not what’s important about playing and writing music. It’s the opportunity to make a positive statement on behalf of humanity that I play music. I feel everyone in any society appreciates some sort of music, and it’s a way of bringing people together in a manner that’s not possible in many other activities.

Finally, you’ve also played tenor saxophone, violin, trumpet and, occasionally, piano in your career, but alto sax is the instrument most people associate with your music. Why did you choose it?

That, again, is because of Charlie Parker. When I first heard what he was doing, there was an energy and a joy in his music that immediately attracted me. It was the reason I began on the alto, and it’s still the reason why I’m still playing and writing now.”

2 Comments

Leave a Reply