It’s August 1995, and R.E.M. is in a state of collapse. Drummer Bill Berry is in the hospital undergoing brain surgery to treat two aneurysms on the right side of his brain (one of which ruptured while he was performing on stage), bassist Mike Mills is undergoing emergency abdominal surgery, and singer Michael Stipe was diagnosed with an inguinal hernia. In recovery mode, the band was back on the road two months later. This was a bittersweet moment in time. As the band toured around their ninth album Monster, they were writing and recording their forthcoming tenth record entirely on the road. If there was something life was throwing, it was catapulted at R.E.M. in ’95. “It was a super tough year for all of us,” says guitarist Peter Buck. “I had my kids with me, and they were eight months old and within the year, they went from crawling around to walking and talking on the tour.”

Videos by American Songwriter

Once back on tour, the band resumed their regular activity. This included making the music which culminated in the storybook of songs documenting the real-time madness of the past year with New Adventures in Hi-Fi.

“For years, Michael and I would say this was our favorite R.E.M. record,” says Buck. “It was a weird, chaotic year, and we all sat down and wrote songs all year long, and made a record that kind of encapsulated what was going on with us, and the tour, and everything else.”

Born out of a stressful and chaotic year of touring, New Adventures in Hi-Fi was a road album at its core, and R.E.M. was a road-writing band. The band even recorded the track, “Zither,” in a giant locker room bathroom at one of the arenas they were playing. “We were all just sitting around with very little to do, so it was kind of spontaneous in that sense,” says bassist and keyboardist Mike Mills. His favorite Hi-Fi track, “How the West Was Won and Where It Got Us,” was another capture of the band’s musical impulses on the road. “We all remember it a little differently, but I’m pretty sure that Bill and I were sitting out in the studio, and he started playing that drum rhythm. I heard him and was on the piano, so the first thing I literally started playing was that song.”

The track just came out, remembers Mills. “I’m not an improvisational piano player, so I just pretended to be Thelonious Monk for a second in the sense that as he said, ‘there are no wrong notes,’’’ jokes Mills. “I was just going to pretend like I’m some guy who stumbled into the studio and had never heard the song before and decided to bang on the piano, and that was all in one take. The chaos, I think, adds to the mystery of the song.”

The band mostly made songs on the fly, though some were more premeditated like Stipe’s swaggering “E-Bow The Letter.” This song was initially written as a letter he never intended to send, featuring Patti Smith, who also closed out the band’s final album Collapse Into Now in 2011. “We didn’t bring in songs,” says Buck, who hadn’t listened to the album since its first pressing in 1996 until recently, before the reissue, which features b-sides, rare demos, and footage from the tour. “We came together and banged them out. Somehow at the end, it all seemed to make sense. I think ‘Low Desert’ was one song we were playing in the first soundcheck, but everything else was written while we were traveling with Michael scribbling in his book.”

The album reflects the band living, and recording, on the road. “The record really captures that tracks were either recorded live or during soundcheck or two or three in a recording studio,” says Buck. “It was so hectic and there was so much stuff going on during that tour that when I listened to the test pressing for the new reissue, it completely brought me back.”

Now, 25 years after the release of New Adventures in Hi-Fi and more than four decades since the band formed, it’s easier to look back on the musical legacy of R.E.M. In all its twists and turns, one thing always remained constant: the songwriting. And R.E.M. always tried to make timeless records. “When you heard them, you couldn’t say, ‘that was clearly made in 1984,’” says Mills. “On the other hand, New Adventures is very much of its time, which infuses it with exactly what was happening during that year we made it, so I think there’s something that adds to its timeless quality.”

Writing was always a collective process of different approaches, resulting in the inner working of the band being a delicate balance between the immediacy and the instinctive nature of playing a song once or twice and letting it be, or adding to it,” says Mills. “Peter, if he had his way, would record a song once and never look at it again, while I’m very much listen[ing] to it and see what can I do to make it better. Those different approaches, I think, gave us a certain complexity.”

Today, songwriting is not as pressing for Mills, who has been performing rock concertos with a collective of musicians since 2010 and is working on several orchestrated versions of R.E.M. songs. “I don’t have the same sense of urgency that I had when R.E.M. had another record to make,” says Mills. ‘Then, songs had to be written and ideas needed to come forth. I don’t have that anymore, but there are still good songs coming out.” He adds, “Peter’s the opposite. He sits with the guitar and can write songs all day long. I don’t approach things that way. There needs to be more of a reason or purpose behind it.”

Nearly 40 years since the band’s 1983 debut Murmur, Mills looks back on the band in varying increments. “The way I look at R.E.M., we were, especially the first five years, together all the time, we either lived together, or we were always hanging out with each other, and just playing guitar and writing songs all the time,” says Mills. “It’s all we did, so it was just a natural thing that we all fed off each other and finished each other’s ideas, and that was kind of the case for most of the ’80s.”

Now, 25 years after the release of New Adventures in Hi-Fi and 30 since Automatic for the People, it’s easier to look back on the musical legacy of R.E.M. In the beginning, the process was more congealed. About five or six albums in, everyone was older and spread out, living their independent lives. In 1997, founding drummer Berry left the band and retired from music to live a more agricultural life.

“Songwriting became a little less communal, although it was still good when we got to rehearse together,” says Mills of how the dynamic shifted over time for the band. “We still came out of those rehearsals where somebody would just start playing something that we hadn’t worked on up until that point.”

Most bands grow apart, both literally and figuratively, and that makes it more difficult to sustain that kind of working relationship, but R.E.M. was wholly committed to what it did, all the way to the end. “We believed so strongly that the band is going to be our life’s work, our best work, and that we’ve managed to make it work,” says Mills. “Even though we were in different places, geographically—and sometimes different places mentally and emotionally—we still found ways to make it work and that’s one of the hallmarks that make a band last a long time, and create more memorable work. I think if you can maintain that focus, that commitment leads to better songs.”

Songs are the main thing R.E.M. has left behind. “Peter and I always felt that our main focus was songwriting,” shares Mills. “Anybody can learn to play guitar or bass. Michael has a gift, but anybody can sing up to a point. What’s really hard to do is write good, memorable songs, so that’s one of the things I think we’re proudest of, and certainly one of the things we focused on the most.”

Mills adds, “We were really fortunate in the sense that we had three good songwriters in me and Bill and Peter, and we had one of the best lyricist and melody writers of all time with Michael, taking the lead vocals. Those four things gave R.E.M. depth and complexity that a lot of bands who have one and maybe two songwriters didn’t have the opportunity to do.”

Legacy is still a strange concept for Mills, long since the band formed in Athens, Georgia in 1980. “The way that we went about our business, we believed in being honest, we believed in trying to conduct ourselves with integrity and transparency, treating people correctly, and treating people well,” says Mills. “We worked with promoters and record companies, and treated opening bands and the road crew well—all those little things add up to a legacy of how you conduct your business with a serious, solid ethic.”

Buck rarely thinks of the “L” word when it comes to R.E.M. “Almost everything you do, I feel like it’s a failure to one degree or another,” he says. “I hear things that didn’t work or I think it should have been done better. It’s just my nature, but quite often I’m pleasantly surprised when I hear records I hadn’t thought about in years, like New Adventures in Hi-Fi. I haven’t played that record since I heard the test pressing in 1996, so I went through it again and thought, ‘Wow, this actually holds up.’”

As time went by, R.E.M. didn’t look back at the time they were together as a band or the end of their run. “Even for the first five or six years after the band broke up, we didn’t really want to look back because it wasn’t really dead,” says Mills. “It wasn’t gone. We’re a little more comfortable with the idea of having moved on, and now it’s a little less unsettling to look back.”

Thinking back, Buck says he is still impressed by the band’s final opus together, Collapse Into Now. “I had to listen to that a year ago and I never thought about it, but it’s a really moving record,” shares Buck. “It was our farewell record, and we’re just all pleased that we ended at the right time and that we’re still friends.”

Click HERE to listen to the Best of R.E.M.

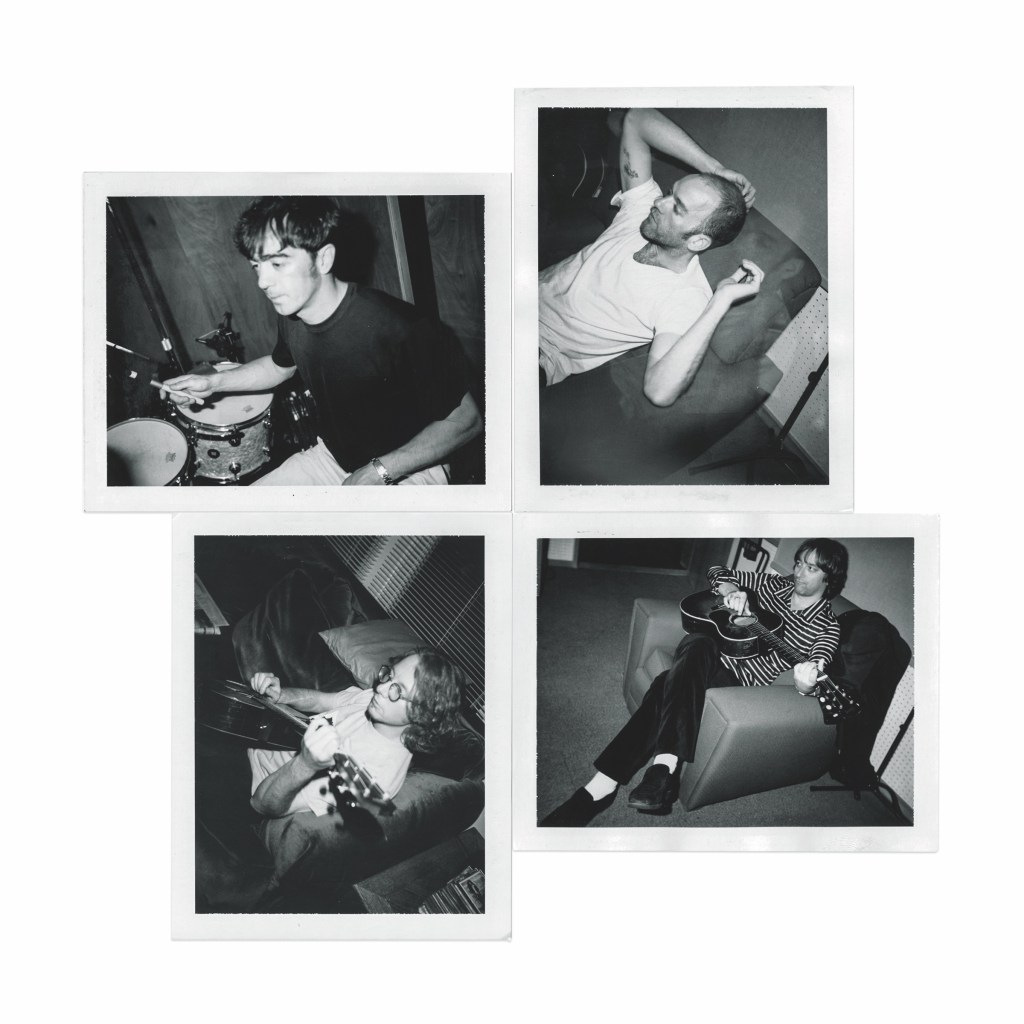

Photo courtesy of Chris Bilheimer.