It was thought that Alison Moyet and Vince Clarke first met when he answered her advertisement for a band in Melody Maker in 1981, but the two met years earlier at age 11, when they both attended the same Saturday music school in Basildon, Essex, in Central London. Basildon is also where Clarke first hooked up with classmate Andy Fletcher to form the earliest iteration of Depeche Mode in the late ’70s, later transitioning to Composition Of Sound with the addition of Martin Gore, and their final moniker with Dave Gahan.

Once Clarke reconnected with Moyet after leaving Depeche Mode years later, as Yazoo, the duo released two albums, Upstairs at Eric’s (1982) and You and Me Both in 1983, before parting ways. From there, Clarke formed Ersaure in 1985 with Andy Bell, and Moyet found her way as a solo artist.

“I had no ambition to be a solo artist,” Moyet tells American Songwriter. “I’d always worked in bands, so I didn’t know who I was.”

In 1984, Moyet released her solo debut, Alf, which went to No. 1 on the UK charts and gave her a first hit single, “All Cried Out,” peaking at No. 8, along with its other charting singles, “Love Resurrection,” “Invisible,” and “For You Only.”

“That was a massive success, which I wasn’t quite expecting,” says Moyet of Alf. “It’s almost like I got a platform too soon before I knew myself as a solo artist.”

From there came another album, Raindancing, in 1987, and what Moyet says was a turning point as a solo artist, her 1991 release Hoodoo, and continued with Hometime (2002), Voice (2004), The Turn (2007), and The Minutes (2013).

Videos by American Songwriter

After releasing her ninth album Other in 2017, Moyet took a brief hiatus from music, enrolling in the Fine Art Printmaking at the University of Brighton in England during the pandemic, and graduated in 2023. A year later, she commemorated the 40th anniversary of Alf with two new songs and reinterpretations of 16 songs spanning her solo career on her 10th album, Key.

“I needed to step away and to reappraise them,” Moyet said of revisiting songs from her past on the new album in the November 2024 issue of American Songwriter. “It’s only when you’ve played live that you understand what the meat and the bones are of the song, what part stays with you, where you can still engage, and what is superfluous.”

Moyet also went deeper into her journey, from scavenging songs from her teenage years for the first Yazoo album to finding herself as an artist over the past 40-plus years.

American Songwriter: Going back to the beginning, and transitioning from Yazoo and writing with Vince Clarke, creatively, Alf was a huge transition. How did songwriting and production begin shifting for you at this point?

Alison Moyet: When I was doing the Yazoo stuff, for the most part, we wrote separately. We wrote “Situation” and “State Farm,” and a couple of others. I remember turning up at the studio. We had done “Only You,” and the record company said, “This has got an amazing response. You should just do an album.” So Vince just went “Got any songs?” And these were just songs that I’d written, like “Nobody’s Diary” and “Winter Kills” from between the ages of 16 and 20, on my own at home, that I then brought to the table. Those songs were already done without any expectation of them ever being recorded.

So when it came to the Alf album, I was kind of a big commodity for CBS [Records], and they did what those record labels did, which I didn’t really understand at the time, which was they found a producer. And the way they found a producer was by going down Music Week, [finding] whoever was the highest-rated producer who would take you on. In Yazoo, we’d never worked with a producer, so I didn’t really know what a producer did.

The studio we worked in [Blackwing in London] had a couple of eight-tracks, but it wasn’t a posh studio. It didn’t have all the facilities, and we were working with the machines that Vince had at the time. So I’d never been in a posh studio or worked with professional musicians, even though Vince was that, but I knew him from school and stuff, so we never saw each other that way. You always felt like you were making it up around the grown-ups.

So I was put in with these proper producers. And for me, at that point, it was just interesting. It was fascinating. I didn’t really know what I was doing, so I did what I always did, which is make things up as I went along, and write words and jam without any expectation or without any pressure, because I didn’t feel the pressure. I didn’t feel it because at that point, no one was being restrictive, and I didn’t know what to expect.

AS: While working on Alf with songwriters Steve Jolley and Tony Swain, was there a song, at that point, that felt the most transitional for you as a solo artist?

AM: “All Cried Out.” I remember them coming around to the house that I was living at the time, and we just sat around my table, and we wrote that in about an hour. It was Tony Swain at my piano, and me just making up lyrics and stuff. It was just easy, no pressure. And then, of course, that was a massive success, which I wasn’t quite expecting. And so then things start changing. Then you’re aware that you’re writing for an album. And that does start changing things up. It’s almost like I got a platform too soon before I knew myself as a solo artist.

I had no ambition to be a solo artist, even though it was reported that I left Yazoo. It was Vince who split the band, and I’d always worked in bands, so I didn’t know who I was. And because I was someone who never really followed other people’s careers, I’d never even gone to an arena concert before I played one. I’d never gone to a pop concert. I had been to punk gigs, but I’d never gone to a theater, so I was on the stage doing that before I even knew what it was.

AS: Did you feel like there was more control by the time Raindancing came along?

AM: With Raindancing, it was more problematic, because then I was amongst strangers. I was living in LA. I liked being there very much, but I didn’t know anybody. I didn’t have a real connection with anyone I was working with, and I felt a bit disassociated.

By this time, I was feeling a bit traumatized about being famous, so I wasn’t in a very happy place. My home life was all f–ked up, and it was just another experience that I later looked at and thought, “Oh, I don’t want to do that again.” It was like I was learning my trade on the job without an apprenticeship.

AS: What was the album where you finally felt in the groove with songwriting, and comfortable with yourself as a solo artist?

AM: It’s ever evolving, isn’t it? That’s the funny thing about music. It’s the one arena where people tie creativity to you. And they assume that you get a certain age and you’re beyond that. You don’t think about that with a writer. You don’t think about that with a painter, or with any other craft. So for me, it was when I started writing with Pete Glenister (third album Hoodoo, 1991) that it became important for me to hone my musical, my melodic, and my lyrical language to leave the stuff of childhood. When I was writing “All Cried Out” and doing the stuff for the Alf album, this was before I’d ever been all cried out. It’s like talking about heartbreak before you’ve ever really had one.

It’s later that you start really living and then that you truly have the meat of something to write about, which is quite funny, because people will associate the big showboating, or the hyperbole, the big noises with passion, when we know so often that pain and all those things are often platformed in silence, in whisper, and monotone. These are the kind of things, later on, that started becoming important to me.

In some ways, I saw being a singer as limiting, because you were always expected to showcase the voice, when sometimes it was the melody or the emotional, or the lyric that was more significant. In showing fidelity to those, it didn’t require showboating.

So that was a struggle for a while, where people think, “Oh, can’t you sing anymore?” These are choices. This noise is a choice.

AS: Then, you’ve also collaborated with other artists. Do you prefer one over the other—co-writing or working solo?

AM: I do like to write with other people. I’ve had two big, significant co-writers, and that would be Pete Glenister (Hoodoo, Essex). He was a very important writer for me. Then in the latter years, Guy [Sigsworth]. It felt like a real meeting of equals. We didn’t edit each other. My domain was melodic and lyrical, and he built up these wonderful sound beds. And that was a perfect setup for me. Sean McGhee, whom I’ve written with on this album (Key), we’ve also written “Reassuring Pinches” and “The Rarest Bird” (2017), which are very important songs to me.

[RELATED: Alison Moyet Returns with the ‘Key’ to Celebrating 40th Year as a Solo Artist]

AS: How long were the two new songs you wrote with McGhee on Key—”Such Small Ale” and “The Impervious Me”—in the making?

AM: I was at university during lockdown and graduated in July [of 2023], and had two or three weeks to get two new songs written in time for our recording sessions. How I wrote with Guy [Sigsworth] on Essex and The Minutes is that he would send over a very basic chord progression and rough sections, and I wouldn’t listen to them. I’d go straight into record as I was playing them the very first time, so that I would start singing, jamming, improvising the minute I heard the chord opening up. So I had no idea what the chord change was going to be or what the sections were. Then I would improvise maybe four or five times. From that, construct a melody and a song structure, which I would then write lyrics for. That’s mainly my method of writing.

With Sean being a singer, when I work with him, oftentimes he has melodic information and might do the same thing with a very basic track and a scratch melody. Then I will go back and embed the melody that he’s provided into my head to suggest words, edit, and transfer a couple of the bars over to put in another section.

“Such Small Ale” was a track that he’d worked on with Richard Oakes from Suede, purposely for this project. So I wrote that one as described. Then, when it came to looking for a second song … I’m really bad at organization, bad at filing, and I have loads of music files. When I went back to Sean, this (“Impervious Me”) was something that he’d sent me in 2013 that he’d had absolutely no memory of whatsoever.

I like those things to be floating around, so that when you’ve got a particular subject matter or a lyrical idea, you can pull from this library of tracks.

AS: You sing Let’s pack off the ghosts / So late to their beds / With a hand-tied of lavender / To gentle their rest on “Such Small Ale.” What is the story behind this song?

AM: With both of these songs, they do kind of have meaning. Sean and Richard thought that was one I’d least connect with, because of the funny time change, but for me, I live in the grid. I’m safe in a grid. My chaotic ADHD nature needs a grid, and so for me, I didn’t even notice any kind of schism in the time signature. The fractions work perfectly well for me. And once you’re in there with the lyric … I wanted to write around the basis of “Such Small Ale” and what that means to me. I love all things Middle Ages and Tudor, and messing that language up a little bit. So I thought it was a good metaphor.

“Such Small Ale” is very much one of those songs that deals with sweating the small stuff. These are the subjects that you’re faced with when you are my age, at 63. You have spent so much time fighting over just bollocks, just rubbish, that even when you win a point, nothing is won. And you’re running out of time. We can either spend the rest of the time with this ridiculous, pointless battle, or we can just get out from all of this grief that we pile on ourselves and feel the sun on our bodies, and forgive one another and be accepting of one another.

im·per·vi·ous: not allowing entrance of passage

AS: “The Impervious Me” seems much more autobiographical.

AM: “Impervious Me” is much more of a reflection of where I’ve arrived at my age. In a long career, you deal with coming to the fore and then dropping out, coming to people’s notice, being completely irrelevant, being a part of the zeitgeist, and being discarded. If you are an artist, none of those things should affect your engagement with what you do. For me, being famous, or any of that stuff, that’s the bad payoff. That’s the downside of having luck with music. You have to get to this place where you trust your voice and you’re accepting.

I know that my best songs are not the ones that got the biggest platform or have sold the most copies. They are often buried, and that’s all right. The whole idea behind “The Impervious Me” is that this is who you have to be. It’s who you have to be to survive in this world, and to continue to be a creative. You have to allow the craft and the growing, and the development to be your end game. You can never, ever trust in the fact that anyone’s going to give a f– k.

And so that is who I am now. I am the impervious me.

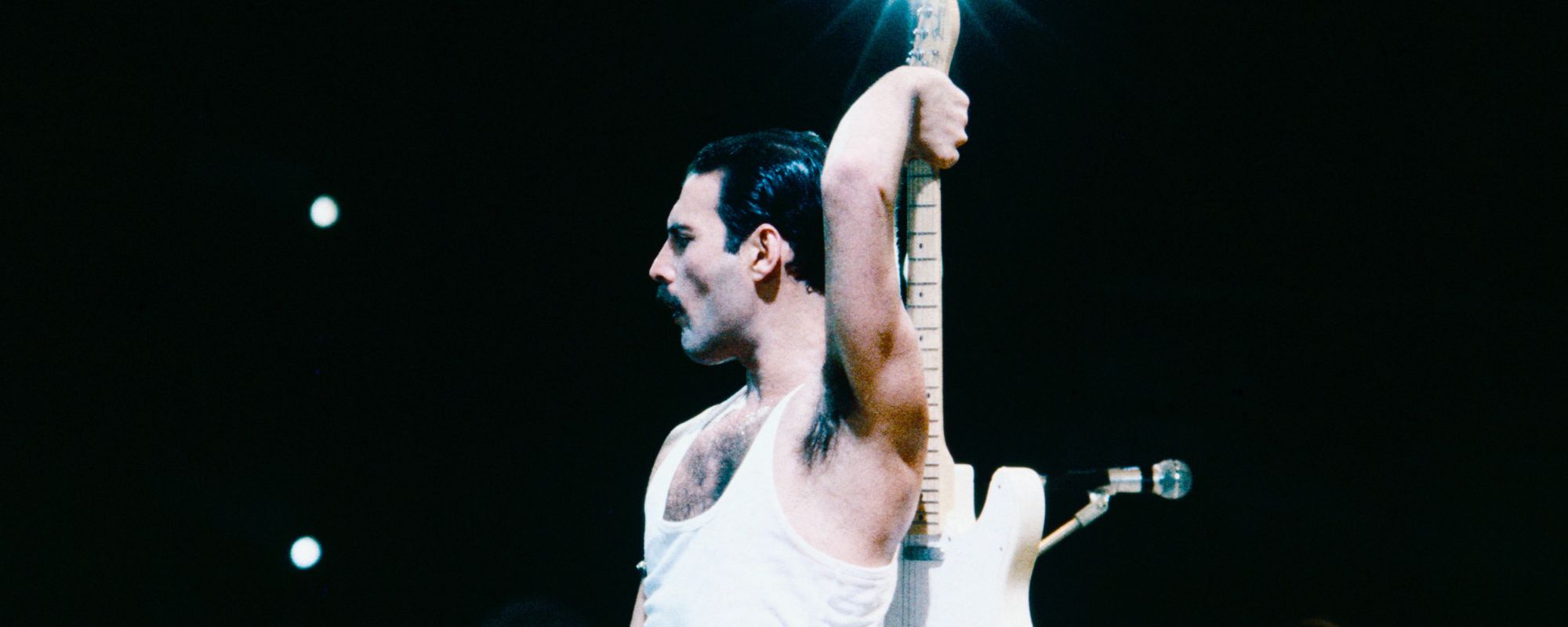

Main Photo: Harry Herd / Redferns

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.