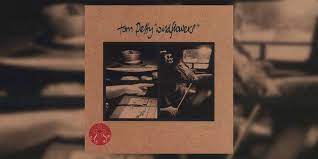

Tom Petty, in his own words, on this essential song which was the finale of Wildflowers.

Wildflowers. Already it’s the stuff of legends. When creating it, he’d already ascended to that mythic ‘Toppermost’ of which The Beatles spoke, and done so repeatedly with remarkably authentic, heartfelt real-time rock and roll, forever evolving but never abandoning that essential fire. For Wildflowers, he tapped into the source so directly that a multitude of songs flooded out of him in a veritable torrent of creative energy. Wildflowers, when under construction, was too small of a frame to contain the fullness of his creation. Its formation was not unlike that of The Beatles White Album in its profusion of songs in every side, shape and color–short simple songs, complex epics, traditional, expermental, rockers, ballads, funny, sad–a whole universe way too expansive for any conventional LP. That remarkable abundance of material for The Beatles became a double album–the first and only one ever by this band–and revealed that their creative powers were sparking at full capacity. To pack so much artistry and expression into that one space was evidence of artists unchained in their abilities.

Videos by American Songwriter

But while The White Album was the result of four songwriters separately writing a lot of material, Wildflowers came from Tom. He wrote “You Wreck Me” to Mike Campbell’s chords, but the words and melodies all came from him. What he did is similar to Michelangelo, who, when asked to add some art to the Sistine Chapel, proceeded to paint its entire ceiling and walls with the fullness of his genius, overflowing with creativity.

Yet in that opus, there’s some undeniable madness at play. Which is not unusual in the creation of the greatest art. There’s little question that Brian Wilson walked that line when creating “Good Vibrations,” which was more like the creation of the Sistine Chapel paintings than that of a hit single. The result was a masterpiece.

Whereas Wildflowers does not reflect madness, or an artist unmoored from the harbor with no clear destination. It is a phenomenal tour de force of songwriting greatness exploding in every direction at once. Yet there’s a gentle calm at its core, a sense of hope and even joy, which was especially projected by its final song.

Wildflowers emerged like a revelation, and was staggering to behold. Yet Tom took it in his easy, happy, humble stride. Here he was overflowing with songs, all beautifully pure and powerfully realized, and all timelessly unified by his big heart and passionate soul.

t this stage in a rock and roll career, especially if there’s been some serious success, the common pattern is to go downhill, creatively, to lose that spark, the electric connection to the source. Leonard Cohen said it’s the same reason you never see matadors older than 30; it takes a lot of energy, audacity and luck simply to survive in this kind of work, much less reach the realm of lasting greatness.

Yet with Wildflowers, Tom not only expanded his substantial songbook profoundly, he did so with joy. Little did we even realize then the bounty of songs written and recorded for this one album which weren’t included. (But came out on the She’s The One soundtrack, and in the great collections of Wildflowers songs now released). The man was on songwriting fire.

But where does one end such an album? What song could possibly serve as the last one to be heard about all that?

The Beatles had a similar quandary when making Sgt. Pepper; the challenge of creating a finale song that is as chromatic, vivid, brave and compelling as all the songs which preceded it. Once Lennon had written most of “A Day In The Life,” it became undeniable that it would be the perfect closer. The orchestral ending of this ending song remains one of the most experimental and dramatic conclusions of any Beatles song: the now-iconic instrumental chaos that simmers and builds, growing in dissonant intensity and expanding thundering chaos. It grows perilous sounding before being resolved to a big E major chord, played on many pianos and other instruments all at once.

Tom’s final song was unlike all the other songs he wrote for the album – mostly just his voice and piano – and an orchestra. But the use of the orchestra on it is the very opposite of thunderous dissonance it’s a beautifully tender and poignant underscoring of the emotion and message of the song. It’s much closer in tone to The Beatles’ final song on the White Album, “Good Night,” the gentle lullaby Lennon wrote for Ringo to sing. It is also orchestral, sans rock band, though much more lush than “Wake-Up Time.” It also shares the distinction of having spoken words in it, as does “Wake Up Time.”

About that, Tom told me he was unsure why he spoke lines in the song, but it just felt right. Like Ringo’s sweet adieu, Tom’s spoken words are delivered tenderly, like reading a nighttime story to a child. Yet that child he was addressing was himself. This wake-up time was his; the parental part of himself urging his inner child to stop being scared, and accept that it was time for a change.

The orchestra was arranged and conducted by Tom’s friend, the late Michael Kamen. Attending the orchestral session was one of Tom’s most shining moments; he delighted in listening to a mix of the orchestra alone playing his music. It was a dream beyond any dream. That boy playing all day in the Gainesville pine straw now was watching an orchestra play his music. Follow a dream long enough and it can come truer than you ever imagined. “You follow your feelings, follow your dreams.”

“You’re just a poor boy alone in this world…

You’re just a poor boy a long way from home

And it’s Wake Up Time

Time to open up your eyes

And rise

And shine”

It’s essential Tom: realistic and earthbound, but also hopeful and transcendentally melodic, it offers advice to a dreamer. And that dreamer is him. He’s singing to himself, and putting this truth into song, as songwriters do, so that he could maybe get the message himself, at long last: To rise. And shine.

It’s one of his most beautiful songs and so distinctively Tom, radiating with a tenderly whimsical bliss alive in the sweet simplicity of its melody. To record it without wrecking its purity, he followed the same path Lennon took when recording “Imagine.” Though the great Nicky Hopkins was the keyboardist on the Imagine sessions and played on several takes of “Imagine,” the pure simplicity of Lennon’s piano-playing was what was needed.

Tom, of course, has Benmont Tench, one of rock’s greatest keyboardists, always at the ready to provide the perfect part. But Tom played the piano himself on the track for the same reason as Lennon. To provide the pure, solid foundation.

On the album, it comes as the finale after the amazing and epic “Crawling Back To You,” in which Tom has been crawling through the briars and battlefields so much that he’s got “dirty hands and worn-out knees.” He’s exhausted by exhaustion itself, and perpetually worried beyond reason. But he catches himself. In “Wake Up Time” he stops crawling, and starts rising. And also shining. Yet it’s sparse. It’s not about any bombast or battle-torn barrage; it’s about calm after the endless storm, and it’s essential Tom: still sunny and forever hopeful. Even then – before his angel dream of joy with Dana had been dreamt – he wasn’t about to break any of the hard promises he’d made. Even as American girls and boys in corduroy pants forever revel in their abandon, he reminds them and himself not to give up hope, and not to stop thinking there’s a little more to life somewhere else, even still:

Yeah, you were so cool back in high school, what happened?

You were so sure not to have your spirits dampened

But you’re just a poor boy alone in this world

You’re just a poor boy alone in this world

And it’s wake up time

Time to open your eyes

With no guitars at all, just Tom’s piano and singing, Mike on bass, Ferrone delicate on drums, and Michael Kamen’s orchestra, Tom closes Wildflowers with a warm and gentle smile.

The following conversation with Tom about the writing and recording of “Wake Up Time” was conducted for our book Conversations with Tom Petty, and came in the midst of a discussion about the Wildflowers album, which ends with two of his most powerful songs:

TOM PETTY: I wrote [“Wake-Up Time”] on guitar and we cut it that way. And then we weren’t quite satisfied with it, though it was pretty good.

So then Rick [Rubin, the producer] said, “Why don’t you play it on piano?” And I thought, “Well, damn, I’ve never played it on piano.”

And he said, “Go out and see what comes if you start to play it on piano.”

It took me a little while to figure out how to play it on piano, because I’m not so great on piano, in terms of playing it on a track. I worked it out, and he said, “Okay, we’re gonna cut it with you on the piano.”

And I said, “Well, Ben’s here.” So then they got Benmont out. And they thought, “No, he plays it too good. Like, we don’t want it to be that good. We want it to be like you play it. Very simple.”

So I did it—with me on piano, [Ferrone] on drums, and Mike on bass. Mike sat in the control room and played the bass.

It’s touching how you speak the title in the song, instead of singing it. It’s your only song that I know of in which you do that.

I don’t know why I did that. But it seemed to work better than singing it. You know, you write so many of them, and you hope for something like “Wake Up Time.” [Laughs] And now and then you get it. And that’s enough inspiration to keep going. I’m going to keep doing this, because I want something else like this.

Did you write that late in the album?

No, it was fairly early on. I wrote it around the time I wrote “It’s Good To Be King.”

Did you know at the time it would be a good closer for the album?

I always did think it would be the end. I wasn’t sure what would be the beginning, but I knew that was going to be the end, and that I was gonna work toward that. And that would be the finale. Of the double album. So that was kind of a good thing to have in your back pocket, knowing where you were going.

So, God, you talk about your shortlist of things you’ve ever done. That song is just one of my best songs. I was very pleased to get to play that to Denny Cordell, not long before he died. I hadn’t seen him in many a year. And he came down to the studio and he listened to the album and when he heard “Wake Up Time” he was really taken by it. And he said, “You know, TP, that’s not like anybody. That’s your thing, man. That’s your thing. And you should be really happy, because you’ve created something which is your thing and nobody else’s.”

And I kind of felt like that. That he’s right, and I felt really good about that, and I’m glad I got to come full circle with my mentor, who really guided me into this business of writing songs. To get that approval from him, so many years later, meant a whole lot to me.

We came back to playing that on our last tour. We only played it a couple of times. And I just thought it was too delicate a number to try to play it in an arena. And then I rethought that, years later, and I thought that I could come out with a guitar, just me and guitar, and get that song over.

So we came back and that’s how we did it. For the most part, it was just me alone with the guitar. And it really worked. It was easy to sell it in the arena, because bringing it down to one instrument really got everyone’s attention. So when the band finally did fall in, it really made a big impact. So it worked that way.

I am very happy with that one. It will always mean a lot to me.

Michael Kamen’s orchestration is beautiful.

Yeah. God bless him, Michael. He was a very talented guy. He was a friend, too. We brought him in to do the string arrangements and the orchestra. And he was really great. We’d go over to his house, and he’d play us his ideas on a keyboard. Then we’d give him our input, and he would make it all work.

And then, when we came to record it, right there on the floor, he could make the changes. If something was working or not working, he could make adjustments. It was done really well. I miss him. He died recently. [November 18, 2003]. It’s a shame. He was a really great musician.

So you were in on the sessions with the orchestra?

Yes, Mike and I went to the string sessions. I was right on the floor. It was a thrill. Anytime you get to work with an orchestra, God, it’s a thrill. Something I could have never have dreamed of in childhood, that I would have that kind of experience. Being in there with all those instruments and that great sound. It’s really impressive to write something and then hear an orchestra play it. [Laughs]

And we didn’t have to have a lot of changes; it was pretty well worked out. He was very good at getting what he had in his head down.

And God, what a great arrangement he did on that song. Somewhere I have a tape of just the strings from that. I used to play that around the house.