To commemorate the 82nd birthday of the greatest and most important rock photographer of all time, we bring you Part 2 of our tribute, this one about photographing The Doors, Crosby, Stills & Nash, and Woodstock

This is Part Two of our tribute to Henry Diltz on his 82nd birthday.

See Part One here.

We pick up the story as Henry is explaining that he teamed up with art director Gary Burdon to create many album covers. None of it was calculated to intentionally preserve historic visuals of rock and roll; all simply happened in the moment, often by “accident,” as Henry said..

Videos by American Songwriter

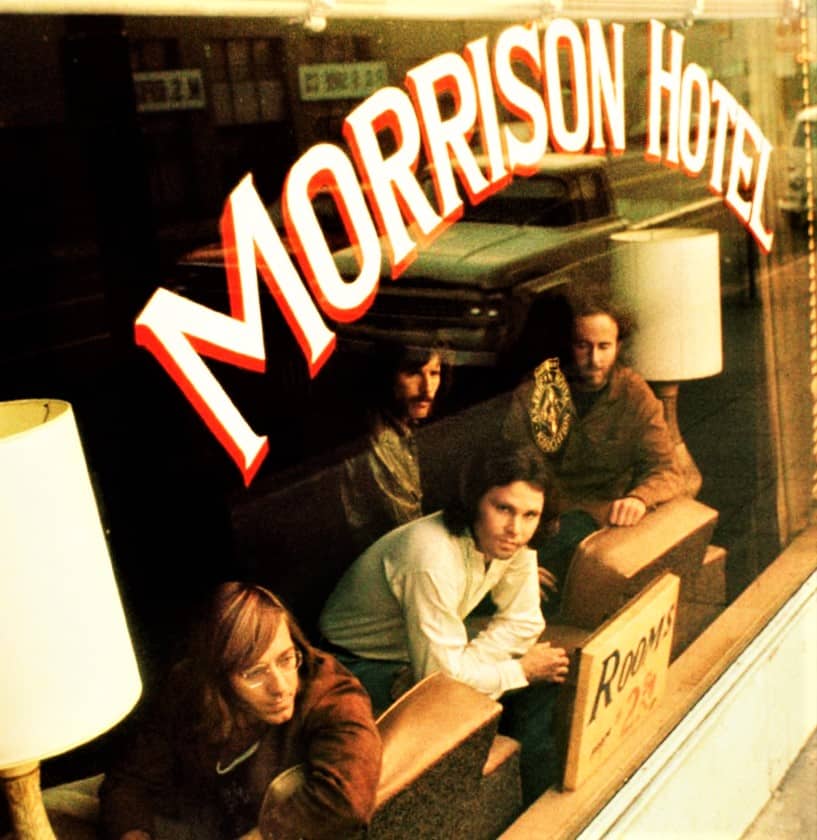

To shoot the cover of Morrison Hotel, for example, he and the band brainstormed about a potential title, when keyboardist Ray Manzarek mentioned a transient hotel he saw near Skid Row in Downtown L.A. It was the Morrison Hotel, at 1246 S. Hope Street. They hopped in their cars and drove there; Henry arriving first with Gary to photograph the old façade before the band arrived.

The idea was to shoot the band inside looking out, using the window as a frame. They asked the clerk there if he would mind if they took a few quick shots. He did. He said it was not allowed. But these guys were not to be so easily deterred. They waited outside till they saw the guy had left his post momentarily, at which time the four Doors ran in, and Henry got the shot.

“Jim [Morrison] lived behind his eyes,”said Henry, “and nobody really knew what went on behind those eyes. He was a poet–enigmatic, and bemused.”

Soon every band wanted the kind of shots Henry Diltz was taking. Even the Monkees, formed as an imitation-Beatles TV band, wanted the Diltz touch, as Henry recalled:

“One day in 1967 I got a call from a guy asking me to go down to The Monkees’ TV show at Gower Gulch. He said they’d pay $300. And that’s what happened–I’d shoot, and then they’d take the rolls of film, undeveloped. And kept them.

“To this day I don’t have the rights to those. What happened is they used to have older guys shooting photos – like newspaper photographers – and the Monkees weren’t comfortable with them, they weren’t’ hip, they weren’t part of the scene. So they brought me in.

“I’d go there in the morning, spend the whole day. You couldn’t shoot when they were shooting, because the click would be audible. So I would shoot when they were rehearsing the scene or lip-synching songs. I used to hide among the light stands cause I knew they would never look at those with cameras, so I was safe.”

Becoming the official photographer for Woodstock, despite its retrospective glory, was as uncalculated as his other famous forays. He accepted though he had no idea whatsoever what it would entail.

His friend Chip Monck, a lighting designer, then living in Woodstock, New York, called him in 1969 and said, “Henry, we’re gonna have a big show here. You should come.” Henry told him he couldn’t afford it. Monck was the MC of Woodstock; his announcements from stage are preserved in the movie and record album.

The next day Woodstock producer Michael Lang called Henry. “Chip said we need you,” he said. “I’m sending you a ticket.”

Henry arrived at Woodstock–which took place on Max Yasgur’s farm in Bethel, New York–three full weeks before the concert would commence. Not only did he never anticipate the scope of what Woodstock would be, he had so much fun living with and photographing the beautiful young people preparing for the show in this great setting that he wasn’t thinking ahead.

“I forgot there was even gonna be a show,” he said. “I was busy photographing all these hippie girls bringing lunch and the hippie carpenters nailing planks. It was a great little village.”

When thousands began flocking in and sitting in front of the giant stage, he caught on to what was happening. And loved it.

“[Woodstock] was an amazing event,” he remembered. “I saw it from onstage and backstage, so I could see the flurry and the hurry of it all. People running around trying to keep it going, get the next act out there, because we have 400,000 people out there waiting! And it got crazy, you couldn’t drive anymore, the roads were all full.

“I had a little rooming house a mile down the road but I couldn’t go home after the first day because people parked their cars on both sides of this little country road, so there wasn’t any room for anyone to drive down the road anymore.”

Although he came to recognize that Woodstock was way more vast than anyone could have planned, he had no concept of its actual size until he saw a newspaper photo.

“It was an aerial view,” he said, “and we were blown away! That’s us? From where we stood it was like a giant sea of people. It went for as far as your eye could see in every direction, a hell of a lot of people.”

Despite the legendary expressions of free love blooming there, Henry focused on the job at hand.

“I was diligently occupied photographing everything that would happen,” he said. “It was like a feeding frenzy–you look around and there’s John Sebastian backstage in his tie-dies playing and singing and there’s pretty girls dancing and there’s Grace Slick and the Jefferson Airplane sitting on the edge of the stage in the afternoon sun, and do you take all of that or do you take photos of Joe Cocker, who is onstage performing?”

Henry, which the world came to know, did a masterful job of preserving the visuals of Woodstock–all the color, the energy, the music–visuals which went a long way in establishing for the world the character of the “Woodstock nation,” as it was known.

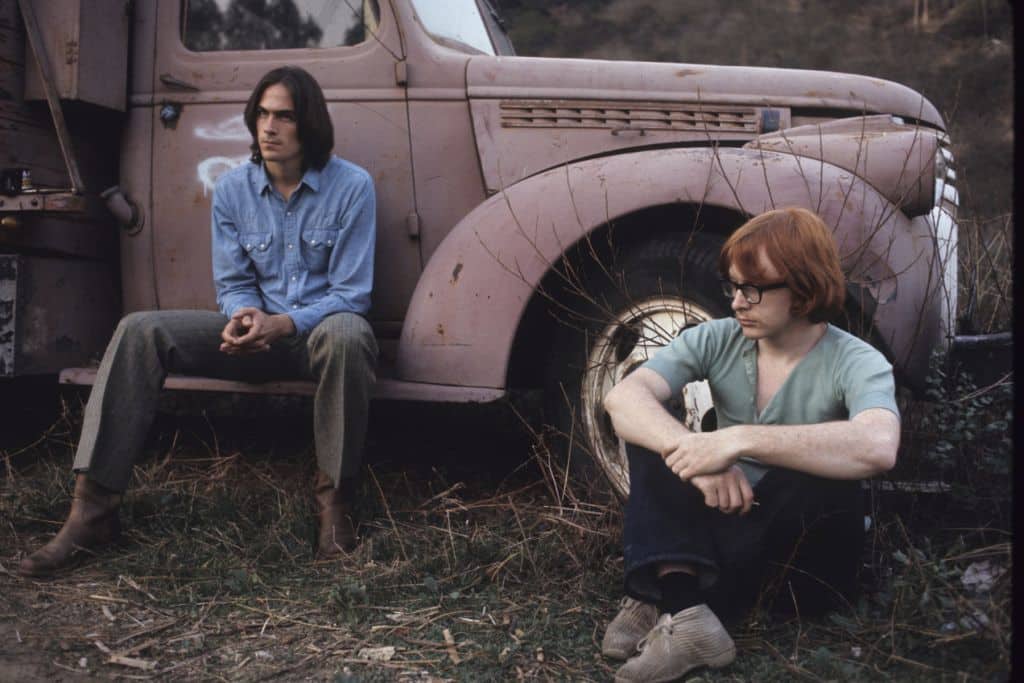

Henry was already a friend with Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and David Crosby, who performed at Woodstock with Neil Young. When they were forming, they’d often perform at people’s parties and astound their friends with their amazing harmonies on the Beatles’ “Blackbird” as well as their own songs. Henry would be there snapping shots, so when the time came to shoot a cover for their eponymous debut, they jumped in a car with Henry and Gary to seek out some locations for an album cover shot.

Like almost all of Henry’s famous photos, this iconic photo happened again by accident, when they discovered an old abandoned house off on La Cienega on Palm in West Hollywood, which had an old couch in front. It became one of his most famous photographs ever.

“When I took this photo,” recalled Henry, “I wasn’t sure it would be the perfect photo, but I knew it was very satisfying to me, the three of them on a couch. It filled the frame so nicely and was so balanced. It’s all a matter of mathematics and symmetrics so that it’s balanced.”

The famous cover of James Taylor’s Sweet Baby James was also accidental. Although the bucolic photos seem to have come from a photo session at a pastoral Massachusetts farm, in fact they’re the product of an afternoon session in Burbank with Henry.

“[James’s manager] Peter Asher asked me to come to his house,” Henry said, “to take black & white promo shots. But the light wasn’t good there, so I suggested we go to Cyrus’ place – he lived them at the Farm on Barham Boulevard [no longer standing, it was situated on the ground behind what is now the Oakwood Apartments] . There were sheds and barns there, and I love shooting around barns, because there’s that old weathered wood. And the way the light comes in the windows is so good.

“[James] was wearing a blue work-shirt. He was leaning against stuff, we were talking, but not too much. I didn’t really know his music then–nobody did.

“When he leaned on that post, that looked perfect, and I took a few black & whites, and I said, ‘Wait a minute, James, I wanna get a few color shots,’ and reached down in my bag for my other camera. I just did that because I wanted to put that in my slide show, so I took half a dozen color shots. And those were the ones they used.”

One of the few exceptions to Henry’s happy accident method was the shooting of The Eagles’ Desperado, for which Gary envisioned the look of an old Western movie.

“They told us it would be a cowboy record,” Henry remembered.”So Gary got some cowboy clothes from Western Costumes and some guns. We shot it at an old ghost ranch out in Agoura. As usual, I just shot everything that happened. Gary said, “Shoot everything you can. Film’s the cheapest part.” And as The Eagles played cowboys and pretended to have a gun fight, Henry caught it all, showing there’s really no kind of photography he can’t do.

Though mostly associated with California artists, he’s also shot many artists whose music was made far from the Golden State, such as Paul McCartney. Henry knew Linda McCartney when both were photographers in New York, prior to her marrying Paul. One day sin 1969 she called.

“She asked me to shoot some pictures of Paul and her,” remembered Henry, “for the songbook for Ram. She said she couldn’t take photos of both of them, so I spent the day with them in Malibu taking photos of them and their family, their kids.

“At the end of the day I did a black & white portrait of just the two of them. And they liked it so much they rushed it off to Life magazine for a cover. I didn’t know it was gonna be a cover; I’d just been shooting all day. Life had wanted to use a Beatles picture, but it was a story on Paul, and Paul wanted the photo to be just of him, cause he had just gone solo. And they had one more day to get a better photo. So Linda didn’t tell me, but she got what she wanted.”

These days, in addition to take new photos, he’s selling a lot of his classic ones. With Peter Blachley and Rich Horowitz, he’s opened several Morrison Hotel photo galleries around the country, which sell fine-art prints of his own work and that of other rock photographers.

The first gallery was in the Soho section of New York, and the second in one-half of the former CBGBs club in the Bowery.

Here in Los Angeles, it’s in the Sunset Marquis hotel in West Hollywood. And there’s also a Morrison Hotel Gallery in Maui.

He’s also created many great books, most recently an extraordinary collector’s item book created by Genesis Publishing in the UK, California Dreaming, of which a limited amount of signed editions were created. Used copies on Amazon are being sold for upwards of $1200.

Henry’s photos are also strewn beautifully through Harvey Kubernik’s classic book of Laurel Canyon history, Canyon of Dreams.

And with the acclaimed writer Dave Zimmer, Henry created Crosby, Stills & Nash, The Biography.

Henry Diltz, in his visual expedition into the heart of the music, preserved the magical genius of this great transitional American era. And although the musicians who created that music have aged, their music is untouched by time, the spirit perseveres, and those great photos by Henry Diltz remain.

Yet Henry isn’t one ever to rest on his laurels. He stills looks with wonder at his remarkable career.

“It’s funny how I got into photography. I didn’t go to photo school or study. It fell into my hands. I became one without even wanting to be. And I still love it as much as ever.”

Though he started taking photos with film cameras, and thought at one time he’d never change, he’s fallen in love with the unlimited potential of digital photography. Not only does he use professional model Canon SLRs, he also loves Canon’s tiny but amazingly high-quality Powershots.

“These little camera are amazing,” he said. “It’s a magic little thing. I take hundreds of pictures every day. I take more now than I ever did.”

For more information on Henry and his work: www.morrisonhotelgallery.com