Featuring the lunacy of conventional thinking, being walloped by song, and the realm of fast decisons

A few years ago, he left a message about this interview, but not before first identifying the short musical passage on my voice message. It was only a few measures long, but it was haunting. Few people had any clue what it was, nor seemed to care.

But when it comes to music, as those who know him already know, Jon Brion cares.

When he called, after hearing this music once only, he identified it perfectly: “Chet Baker, one of his last recordings, on Elvis Costello’s ‘Shipbuilding,’ 1983.”

Later I checked the year. Of course, he was right. This is a guy who knows his music. Which is one of the many reasons he’s been so much in demand over these years. Not only as a producer, but also as a multi-instrumentalist session player, songwriter, and film composer. His score for Magnolia established him as a seriously expressive film composer and led the way to his work scoring many films, including Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Lady Bird, Step Brothers, Punch-Drunk Love, This is 40 and many others.

He’s produced albums by Fiona Apple, Aimee Mann, Rufus Wainwright, and Robyn Hitchcock, and had just embarked on a new David Byrne solo project when we first spoke.

Videos by American Songwriter

A remarkably creative guitarist, especially in terms of weaving together intricate parts, he’s also fluid on keyboards, vibes, drums, Bouzouki, ukulele, lap steel, bass and other instruments.

He was a session player for a long time before becoming a producer. He’s played on albums by everyone from Taj Mahal to Tenacious D to Jellyfish and beyond. Known to give far more in a single session than most session players do in a year, he’s taken tracks in progress, privately layered them with a cavalcade of instrumental coloration, and handed them back to the artist and/or producer saying, “Here you are — any of these ideas you like, use.”

“I guess that’s not

usual session guy behavior,” he said. “I never even knew how odd

it was until the last couple of years. I’ve spoken to a few friends who

are among the best all-time session people, and they play just drums, or just guitar.

They don’t show up with a truck of instruments and say, “Oh it’s time for

xylophone now!”

His ability to wed a vast vocabulary of musical knowledge with a tremendous and

joyful energy, intimately coloring and molding the sounds of albums around the

songs and personalities of artists, elevated his status quickly. He went

from crazy session cat to one of the world’s

most accomplished and brilliant producers in a short time.

As Aimee Mann said in our pages, “The secret is out on Jon.”

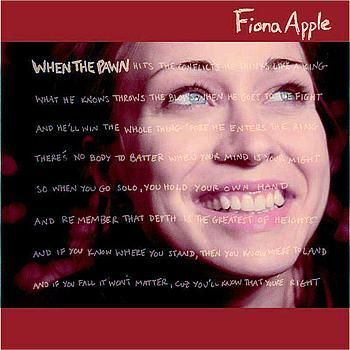

We spoke soon after the release of Fiona Apple’s When The Pawn… [the title of which is actually much longer, the longest album title ever, and is complete below] in 1999, at which time it was staggering, and still is some 21 years later, that his production was created after she played and sang the songs solo.

This approach, which reversed the usual drums-first approach to making records, seemed crazy then. It would be tantamount to The Beatles recording by each laying down their guitar and vocal, then going home for months as George Martin played all the instruments.

But the traditional way of doing it, as Brion said with a smile, was “as much a lunacy as mine is.” His brand of lunacy brought this record to a realm of intimacy most never attain. Rather than create a simple frame into which a song can fit, he built it a custom frame all around the song. He recorded her vocals and piano first, all alone, and then crafted all the other elements — guitars, drums, keyboards, etc.– around that initial performance.

It’s a production style replete with warm, unexpected sounds, wondrous color shifts, and a dynamic range that sweeps through the full sonic spectrum available to humans — from moments in “Love Ridden” that are so quiet and still that you can hear Fiona’s foot on the piano pedal, to passages in “Fast As You Can” that burn so furiously it feels as they might ignite.

“When a songwriter writes something great, and knows that it is different from all the songs that preceded it, there’s a tremendous energy in the performance,” he said, and though it applies specifically to his work with Fiona, it’s the same energy that he brought to David Byrne, Aimee Mann, or any of the other artists with whom he works.

He’s said to come up with hundreds more ideas than necessary, but it’s a profusion of creativity which is exceedingly welcome in the sometimes stifling creative environments of recording studios.

“The whole thing is trying to replicate a feeling of intimacy,” he said. “Maybe not actual intimacy, but that feeling. It’s only in recent years that I’ve learned how to do that.”

Much of what he’s learned he’s already put into practice and proved effective, even though many of his production ideas — such as that drummers should play softly while recording — go directly against the current of conventional wisdom.

“Conventional wisdom would also say that the records that sell the best are the best records,” he said before laughing heartily.

We spoke on a cool, clear Angeleno afternoon, during which he devoted much energy to the pursuit of an anxious gecko that had somehow stolen into his Hollywood home, and which he repeatedly tried and failed to free. Though maybe not as momentous a project as producing Fiona Apple or David Byrne, still he gave it his full attention, which is maybe the secret to his success. When Brion works on a project, he always gives his all to it, even when his motives are misread.

“[This gecko] keeps looking at me like I might eat him,” he said of the elusive lizard, “which, frankly, I don’t want to do.”

AMERICAN SONGWRITER: Your production of Fiona’s “When The Pawn…” is extraordinary, and matches the uniqueness and passion of her writing and singing.

That is very kind of you to say. Fiona is deeply incredible. Just really, really good. It was a pleasure every day to work on the material. She is a total dream to work with. She is the easiest, nicest, most considerate, most forthright person I have ever worked with in a production capacity. No one even comes close.

Fiona shows up on time, sings three passes of the vocal. It’s amazing. She is completely articulate about her likes and dislikes. She’s also able to describe why, in terms of the song, she doesn’t think something works emotionally. A lot of people don’t have that talent, and come shell-shocked from bands or producers they’ve worked with, and not necessarily open to ideas. There are a lot of people who, simply because an idea is not their own, are not perceptive to it. She doesn’t suffer from any of that.

Her songs seem conceived in full conjunction with the production.

I love that you’ve said that. After she wrote all the songs for the album, she handed me a folder with ten songs, handwritten lyrics, the full album title, already in place, and said, “I want to sit down and play these, and then we can talk afterwards rather than talking after each song.” And she played me an album. I sat Indian-style at the foot of this upright piano and she played this stuff. And walloped me. It was so fantastic.

After she finished, she said, “I think I have figured out what I’m good at. I write pretty well, I’m a good singer, and I can play my songs well enough on piano. You’re good at everything else. So I think that’s how we should proceed, and if we are ever off-base, I’ll let you know.” And that is exactly what she did.

I bring this up because people hear certain things on the record and assume I came up with them. Like all the time-changes in “Fast As You Can.” All that stuff was there. All I did was to heighten pre-existing things. In terms of the color changes, I am coordinating all of those, but the rhythms are absolutely Fiona’s.

So you would create the album around her performances, and then play her what you did later?

Pretty much. We tracked vocal and piano to a click track, and then I brought in two drummers we both love, Matt Chamberlain, who is amazing, and also Jim Keltner, one of my favorite musicians of all time. We got the basic tracks and then I would experiment.

She would come in for three hours every day. She would come in, sing, and then listen to what I had done the night before. We would sort through it, and usually she would like about 80% of it. And with the other 20% I would say, “Okay, let me try something else.”

Was there any pattern to the things she didn’t like?

It was always song-based. A lot of people come in with different manifestos, which are sometimes just reactionary things, like, “I don’t want any drum kits in the studio.” She doesn’t have that. It was a song-by-song basis, and we always discussed things from an emotional perspective. She didn’t say, “I don’t think B-flat is the right note.”

We always discussed it in terms of the songs. Like, “Okay, this section of the song is remorseful. And that sound doesn’t evoke that for me. And here’s why — I think it’s too bright in this way, and too jaunty in this way.”

And I would invariably think she was absolutely right. She obviously has very good emotional instincts to write that way. So at some point you have to respect the instincts of the artist.

How much would the lyrical content of her songs affect the production?

Without question, it’s the single most important thing. But I am a songwriter first. All good musicians I know are obsessed with lyrics.

That vocal she would lay down with piano, would you use that as the final vocal?

Sometimes. She is easily one of the most natural singers I have ever recorded. It is nothing for her to do what she does. Occasionally it would change, but not too often, because the production was tailored to the song and to the vocal.

I think the vocal is the

most important thing on the record, followed by the way the record feels and

then how it’s colored. That’s the hierarchy. Performance first,

sonics second.

Would she

play piano and sing at the same time?

Sometimes. We worked

on that, because I wanted a very solid foundation since we were to add drums

after the fact.

The conventional approach to recording, of course, is to get

the basic tracks down, which means getting a good drum track and then basing

everything on that –

I wouldn’t recommend it for most people. But every record should be different. And at the point where humans are not really around playing together, it’s all illusion, so it becomes almost a moot point.

Often when you do the drums first, that can result in a less creative drum track. People try to get drum tracks as metronomically right and as high fidelity as possible. And I actually don’t like the way records made that way feel. I like to hear drummers playing with the songwriter.

I also like to hear the songwriter’s basic instrument on track. Because if you have the songwriter playing it on whatever instrument they are writing it on, you have the DNA of everything in there. Every time.

Any time I have ever been in the studio, and we’re having problems with the groove, I tell the songwriter to go pick the instrument they wrote the song on. Invariably, all the dynamic information, all the architectural information, all of the subtle groove implications and any weird, little, double-timey implications in the groove — it’s all there. There was something that got them to write the song in the first place.

Yet it’s common for producers to eliminate the songwriter’s instrument from the track, the thinking being that you can always get a better musician to play it.

Right. But, of course, there’s another philosophical way of looking at it, which is that there is no more perfect one. There can’t be. There can be a tighter one, but there can’t be a closer one to what made the song happen.

With Fiona, did you ever discuss production ideas in advance?

Sometimes. As soon as she played “Fast As You Can,” I knew exactly what I wanted it to be. I knew I wanted it to be Matt Chamberlain on drums. He can play all this beautiful machine-influenced stuff, but with human feel.

I had a little keyboard in my kitchen, so I played Fiona this very busy bass line idea I had to go with this groove Matt would do. She got completely excited and said, “That’s great! That feels exactly like it!”

When she made her first record, she did that classic thing of being around the studio for twelve hours a day. She didn’t want to do that again, because she felt she didn’t make good decisions after a few hours. And it was true. Her attention span to emotional detail in music is about three hours. But for three hours she was there, she would get more done than most people I know could get done in twelve.

So that was another reason for doing the piano and vocals first. It was to get her stuff done, so I could bring in Matt and work on something during the day, and she would come in at night, listen to what we had done, and if she wanted to make changes, he would be there and the sound would be up and we would do it. It was all fairly organic. She’d be checking in during the process, but I also had her complete trust and complete freedom.

Did you ever ask her to do demos of the songs for you?

No. I don’t think demos should exist.

Why?

Because there is a

beautiful, magical thing that happens when you allow your subconscious to be

part of the work you do. When you are recording, your first take or first

few takes of a song are the only chance where that happens. Immediately thereafter the conscious mind is involved, you’ve heard the

recording of your voice track, you’re now working towards a particular

conscious aim. And how often do people play “Chase the

Demo”? They never quite revive the magical feeling of the night they

wrote the song.

Most of the best

songs I have ever recorded were written while the album was being made.

So that the songwriter says, “Oh, I just wrote this, can we put this

down?” When it’s that fresh and I hear all that emotional excitement

in there, I get excited and I can basically finish all the overdubs in one

session, as soon as the songwriter is done singing.

That happened on both Aimee Mann albums I did. She’d say, “I’ve got a new song — can I record it?” We’d put it down, vocal and guitar, I’d put most of the overdubs on it, and later drums. Most of the overdubs were put on probably forty minutes after she was done putting on the vocals.

Aimee spoke to us recently about working with you, and said that you generate so many ideas that if she picks up on only one-tenth of them, she can do pretty well.

That’s nice. To me, setting up that place where ideas are being generated, that’s something that creative people respond to, and it begets more ideas. Once you have that going, then the intuition has to kick in because you have to start making snap decisions.

Suddenly if there are ten possible ways things can go, you’re not sitting around in a malaise going, “Which one?” You’re kind of excited because there is an energy in the air, and you start making fast decisions, which means better decisions. Getting to that place, that’s what this is all about.

The full title of Fiona Apple’s album known as

When The Pawn… :