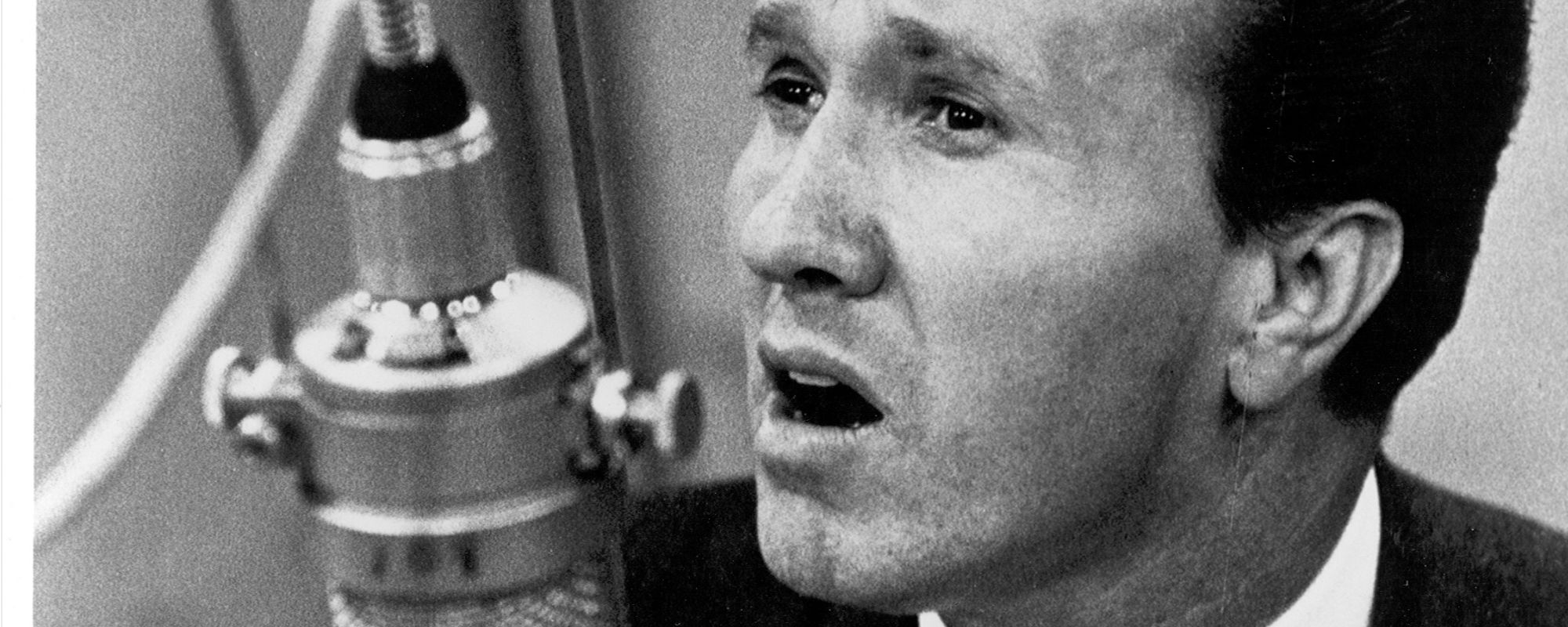

Dar Williams has built a reputation on turning everyday details into something luminous, and her new album Hummingbird Highway (out now on Righteous Babe Records) continues that tradition. The record takes its title from the sensation of speeding through life – moments of beauty, flashes of risk, and fleeting glimpses that pass in an instant.

Videos by American Songwriter

“It’s a road full of vibrant colors and fragile wonders, but also the hazards that come with moving too quickly,” Williams says. That image captures both the urgency of modern life and the energy behind her latest collection of songs.

Raised in the suburbs and inspired early by teachers who encouraged her to look outward, Dar Williams has spent decades shaping her observations into sharply drawn characters and stories. On Hummingbird Highway, those figures emerge in quick, vivid portraits—tiny plays that unfold over the course of a few minutes, carrying the depth of a novel in the frame of a folk song.

American Songwriter Membership caught up with Dar to discuss the creative journey and process that led to Hummingbird Highway.

Dean Fields: Congratulations on ‘Hummingbird Highway’! What creative surprises came up while writing and recording this album?

Dar Williams: At the beginning of 2024, I felt like I had all the songs, but none of what I call the “aha moments” to finish them. I was writing a song about Maryland with Congressman Jamie Raskin, but at one point I realized -aha- that this was a song about Jamie himself, proud son of Maryland! Then I could finish the song. With “The Way I Go,” I wrote the line, “It might not matter much to anyone, but it means something to me,” and thought, “Well, that’s kind of simplistic,” and then thought, “No, it’s deeply true and takes a long time to learn that if something matters to me alone, then it means something.”

Other lines emerged of things that seem self-evident, but are actually hard-earned, like “The way I go, it’s the only one I know.” And then I could finish it. The recording process offered great surprises every minute. I’ve learned to talk through my sense of a song with the producer (Ken Rich is awesome) and musicians, and then step away and say, “Take it, boys!” And Clara. It was all boys and Clara (cellist).

How has your songwriting process evolved from ‘The Honesty Room’ to ‘Hummingbird Highway’?

It’s always been the same! I’ve never written every day. I’ve courted inspiration every day. Some days are all fireworks. Some days are duds. That’s a constant. When I’m starting a song, I still apply the same advanced science of songwriting: “What sounds pretty? What is interesting to me?” And then I ask myself what’s happening in this song, and then, “What’s really happening?” And then there’s a “this is hopeless” moment, and some breakthroughs. And… one “aha” moment pushes it out! I personally have changed enormously, but that’s another thing.

Your songs are rich with detail. How do you know when a song is truly finished?

It’s done when I’ve done the run-through of “is this what I wanted to say?” I remind myself, gently, that I might be singing this song a thousand times, so it’s good to feel set about every line.

You often create vivid characters. What advice would you give songwriters on finding and shaping characters in their own songs?

One thing I’ve noticed is that songs have a voice that can precede the characters. The voice can be bouncy, curious, wind-swept, Baroque, orange, purple. I try to feel the voice and let the characters come out of that space.

Once I have a feel for the world I’m in, I put everything I can think of on a big table in my mind. Like in Teen for God, I had tents from my summer camp, the big lake, my friend Julie’s camp (a Christian horse camp), teenage longing, mean teen girls, authority figures, my Christian youth group, disillusioned atheism in college, Satanic possession movies from the 70s… Not all of it made the song, but I gave [the] narrator all the props and scenery she could use to navigate what was true to her and the song.

Many of your songs balance personal storytelling with broader social themes. How do you decide when to keep a song intimate and when to reach outward?

I lead a retreat, and I encourage songwriters to write the song they’re writing, paying attention to the voice of the song and continuously finding their way into it.

And then I have to heed my own advice! I have to write the song I’m writing. That’s how I wrote “Tu Sais Le Printemps”, which felt very light and romantic, and very different from how I was feeling in the world, but I just kept on accessing a part of myself to stay with the song.

Alan Arkin lived in my hometown and used to speak on career day. He said we all have everything in us, all the characters. I think we have all the songs in us, too, so once a song emerges from the swirling mists, I just stay with that, letting it grow or morph on its own terms (as much as I can).

What drew you to cover Richard Thompson’s “I Want to See the Bright Lights Tonight”?

I’d always sworn I’d heard a live rockabilly version of this song, but I couldn’t find it, so I started doing it that way, and then I wanted to record it. We recorded a bonus bells and chimes version of it, too, because to me it’s the perfect holiday shopping song, “I need to spend some money and it just can’t wait…” I told Richard that I wanted to conjure the chaotic glory of a Macy’s sale in a bedecked Herald Square. He let me change a line about “drunken knights” to “drunken Santas” and sent me off with his best wishes.

If you could give your younger self any advice about making a career—and a life—in music, what would it be?

I am the luckiest person in the biz, because I fell into all the things I would recommend:

1. Find a way to see the world poetically. I did that because I was in Boston, surrounded by actors, poets, musicians, museums, and old movies at the Brattle Theater.

2. Go to a town with a music scene (open-mics, gigs, media, audience), for two reasons: we learn and grow with our peers (and compete with them, sleep with them, collaborate with them…), and also, if our music finds a wider audience, we can grow our careers in music-scene cities, find some business infrastructure, widen our regional touring organically, and have some footing before we even start doing big road trips.

3. It’s crucial to figure out how much money we need and want. I highly recommend the book Your Money Or Your Life. We literally have to build a life around what we need to live on, not shaming ourselves about how music should pay all the bills. Dog walking, house sitting, coffee serving, and lots of part-time careers can be an excellent social and inspirational complement to writing, recording, going to open mics, and playing tip jar gigs as we discover how music will be in our lives, with or without music-based income.

Become an American Songwriter member and get exclusive content, including access to the songwriters behind hit songs by Bonnie Raitt, Ed Sheeran, Morgan Wallen, Guns N’ Roses, and more. Plus exclusive content, events, giveaways, tips, and a community of songwriters and music lovers.

Photo by Carly Rae Brunault

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.