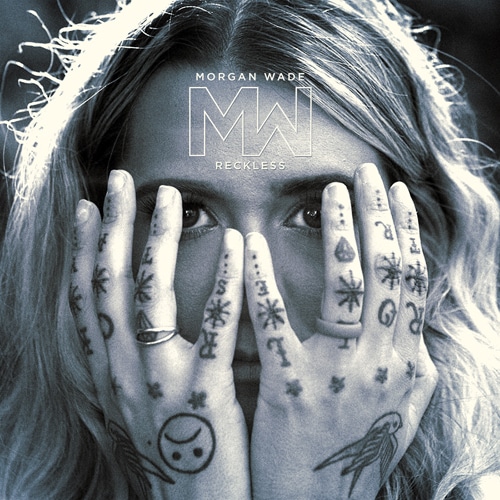

Morgan Wade is an anomaly. She’s covered in tattoos, her fearless eyes straight to the camera, yet her gritty songs are sung with a baby doll/old school girl group voice. The ache, the tears verging, the tone that’s honey melted into moonshine suggests an innocence almost lost, not an old soul siren from the wrong side of the tracks. Broken-hearted and in full possession of the risks of love, as well as the thrill of falling, the rush of it, even the hollow-point loneliness that fills in the gaps, Reckless traffics not in wide-eyed, but eyes wide open reality.

Videos by American Songwriter

Just 26, the Floyd, Virginia native isn’t interested in playing coy. Reckless is frank about erotic desire, about the way hurt tears at the core, how living hard extracts a toll that’s almost impossible to measure; but against acoustic-driven arrangements that undulate like sheets in the wind, the dirty blond or honeyed brown-haired songwriter measures hope into the equation as she delivers unreserved desire from the margins.

“Growing up in the South,” begins the straightforward lyricist, “people are always saying, ‘Well, you’re just having your feelings…’ But instead you’re having a panic attack, or you’re masking something. You have to ask, ‘So, what’s causing that?’”

Reckless witnesses to the washed out, the ones who’ve lived hard and shipwrecked. Rather than playing to the haggard details, she brings the complicated emotional truths instead.

If you were here, I’d sure love to get you hot and lay you down, she confesses in “Matches & Metaphors,” professing Maybe I can move on, but there’s nothin’ to move on from / My body’s on fire, but my face is numb… Or she offers on “Don’t Cry,” as an acoustic guitar downstroke is sprinkled with mandolin, At some point your hero must die, to escape the hands of time / It’s okay to not be alright… Lose yourself and break your heart, it’s a beautiful thing to fall apart.

Wade was told she couldn’t sing growing up. Her voice—too raw, too real—startled people; they told her to be quiet. She knew the music inside her needed to come out. Undaunted, she sang in her bedroom. Alone. She didn’t care, she knew better.

“I’d spent so long being told, ‘Your voice is weird’ by other kids, and it’s such a pivotal time,” she marvels now. ‘They’d say, ‘What’s wrong with you? You can play for yourself, do it at home…’”

With classic songwriter moxie, she reveals the advantages. “And it helps, because you do it for you.”

Doing it for herself offered a freedom few writers can know. She still needed to free herself from every “no,” “can’t” and “whatever.” Her first band—formed off Craigslist—found the young writer in what might be sketchy environments.

“My two friends, who were my age, rolled into this house in the not best part of town, the ghetto really, which wasn’t smart. But we went down into this basement and made music and made friends. It was great doing that, a real lesson, because I’d always known that’s what I was meant to do, but I had no confidence.”

An outlier writer, Wade’s songs were flaming arrows through anyone who heard them. A break-up in college forged her drive and her voice. Being paid in beer and bad booze at gigs, helped grease what would galvanize her reality. By the time she was 21, she couldn’t go anywhere for her “legal birthday,” because everyone had been watching her get drunk for years.

During a trip to New York City, still in her early 20s, Wade started drinking—like many performers, alcohol was liquid bravado—and just kept going. She has a memory of being face down in a parking lot, waking up the next day knowing it was stop or die. She did.

Her writing took on a new clarity. The days suddenly had more light to them.

“I was afraid [being sober] was going to change my writing,” she confesses. “It did. I stopped writing songs about getting drunk.”

At a festival, Wade saw some guys watching her from the side stage; one asked if she had any CDs. Road-wise, she suggested the merch table. Laughing, she now recalls, “One of them was Jason Isbell’s guitar tech.” Exhaling, she marvels, “Since I quit drinking, stuff like that happens all the time. Two days later, I got an email from Sadler [Vaden], explaining who he was—and that he’d like to work with me.”

She pauses for a moment, demonstrating the doubts that had become reflexive. If the skin becomes too thick, she knows accessing her feelings will be impossible.

Sadler Vaden serves as Jason Isbell’s guitarist in the 400 Unit. Understanding the power of wild things, he suggested writing some—making some demos. Having heard it all, Wade listened closely and sensed something different.

“I’ve heard it all,” she sighs. “Everyone wants me to be the next… what? Miranda’s the bad girl. Ashley’s the tattooed girl. I had people telling me I could be the next X, Y and Z… and I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to be me.

“Sadler was like, ‘Why don’t you come to Nashville, and lets just see.’ He didn’t want to turn me into somebody else. He actually wanted to figure out what and who I was.”

“Wilder Days,” which opens Reckless, was their first collaboration. An electric guitar, a shaker and her voice, it’s a plea to not just converge, but ruing the fact she’d never know the person being sung to before they’d settled down.

“It felt good. It’s got more of a rock feel to it, and with my accent I really worried about that,” she says. “Sadler’s a Tom Petty guy. He’s rock & roll, so how was that gonna work? Turns out, pretty well. That song needed to be different. It’s both what I am, and a little bit more.”

That little bit more provides muscle to the tenderness, jangle without becoming folk-rock. Citing Miley Cyrus, Lady Gaga and Lana del Ray as stars she steers by, “You listen to Miley, and she just doesn’t hold back. Lady Gaga, too. They put it all out there.” She reaches for that same candor in her own songs. After chasing the dream, dead-ends, getting sober and waiting for a break, she knows you only win big if you bet big.

So Reckless puts it all on the line, no fear or Fs given.“Honestly, the more exposed I am, the better it makes me feel,” she shares. “There are a million fake people out there, and who needs more of those? Who listens to them? Or believes it? If you’re struggling, and you put it out there, people actually say, ‘I really connected with (whatever the content).’ In making other people feel less alone, somehow I’m less alone. So I give away my feelings, then I get a sense I’m not the only one.”