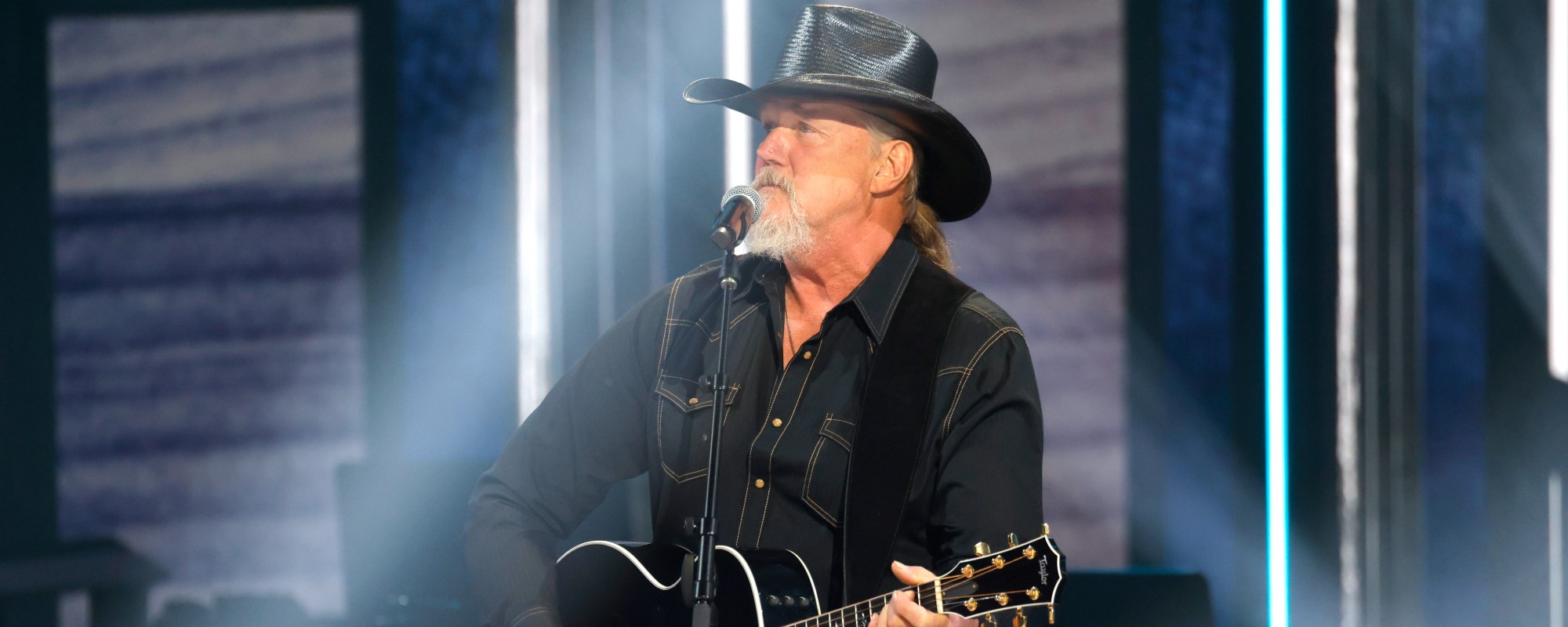

Before DeFord Bailey stepped into the recording studio on October 2, 1928, Nashville, Tennessee, was an up-and-coming metropolis with a reputation for hosting live musicians and performers. By the time Bailey stepped out of the studio, Nashville was officially Music City. The Smith County native had cut the very first vinyl record ever produced in Nashville, marking a historic milestone of a city that would go on to birth countless records ever since.

Videos by American Songwriter

Remarkably, that wasn’t even the first bit of history Bailey had made by that point. After developing a reputation for his virtuosic blues harmonica playing on radio programs like WSM Barn Dance, Bailey became one of the first performers to appear on the newly founded radio show, The Grand Ole Opry. He was the first Black man to perform with the Opry, where he would stay for fourteen years.

When he wasn’t performing on the radio in Nashville, Bailey enjoyed success as a recording and touring artist. His trademark song from 1927, “Pan American Blues”, was one of the first recorded songs to feature a harmonica blues solo. Bailey also performed around the country with notable acts like Roy Acuff, Uncle Dave Macon, Bill Monroe, and other colleagues from the Opry.

He all but retired from music in 1941 after getting into a dispute with WSM about music licensing. Bailey returned to the hallowed stage a few times following his departure. But mostly, he made money through his shoeshine stand and renting out rooms in his home.

DeFord Bailey Made Music City History in October 1928

DeFord Bailey, born in mid-December 1899, died in Nashville on July 2, 1982. He left behind a stunning musical legacy not only as a founding member of the Grand Ole Opry but also as one of the first Black men to achieve tremendous success in Music City—most notably, by being the man who made it Music City after recording eight harmonica songs for RCA Victor in the early fall of 1928. He performed with some of the most famous players in the business and was a fan favorite on the Opry and beyond. His legacy is immeasurable, but it’s not one without hardship.

Despite being a beloved member of the WSM radio program, The Grand Ole Opry, Bailey was no stranger to the racism permeating the American South and beyond in the 1920s. He often faced segregation while on the road, struggling to find lodging or dining accommodations that would serve him as a Black man. The swiftness of WSM’s firing of Bailey and the fact that he lived the rest of his days as a shoeshiner and landlord were additional, unfortunate testaments to Bailey’s lost potential. Fans dubbed him the “Harmonica Wizard,” yet his final years of his life were anything but magical. He died of kidney and heart failure at 82 years old.

“A harp ought to talk just like you and me,” Bailey once said, per the Country Music Hall of Fame (where he was inducted in 2005). “All the time I’m just playing, I’m talking. But most people don’t understand it. In blowing a harp, it’s just like going to school to learn foreign languages. You got to learn how to make it talk in all sorts of ways. I can make it say whatever I want to.”

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.