While documenting Bob Dylan’s 1975-1976 Rolling Thunder Revue for his book On the Road with Bob Dylan, New York journalist and author Larry “Ratso” Sloman found himself inside a phone booth, connecting Dylan to Leonard Cohen.

Videos by American Songwriter

Dylan’s North America tour featured a collection of surprise guest musicians and collaborators, including Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, and Ronee Blakely, among others. Sloman, who was already a friend and acquaintance of Cohen’s since first interviewing him the previous year, was pushed by Dylan to call Cohen after the two ran into one another in a hotel lobby in Montreal.

“I bumped into Bob and he was shopping in the lobby and said, ‘Hey, call Leonard. See if he’ll come and do a song,’” to a slightly reluctant Sloman. “No, no call him right now,” urged Dylan, according to the writer.

“I’m dialing his number and all the time Bob is literally tugging at my arm,” remembers Sloman, also known as “Ratso,” a nickname affectionately bestowed upon him by Baez during the aforementioned tour. “I say, ‘Leonard, it’s Larry. How you doing?’ and Leonard’s answer to that was, ‘Well, I can’t complain.’ That’s what he would always say. I’m trying to talk to him, and Bob is going, ‘Is he gonna come? Is he gonna come?’”

Eventually, Sloman handed the phone to Dylan so the two could speak without a mediary. “I hear Bob saying, ‘Leonard, how you doing?’ And of course, I hear Leonard go, ‘Well, I can’t complain.’”

Sloman’s account is one of a multitude in his Rolodex of memories, all stemming from his initial meeting with Cohen for a Rolling Stone assignment in 1974, one that would flourish into a friendship that continued for more than 30 years. Left with endless hours of unedited tape recordings of conversations with Cohen through 2005 that had never been heard before, Sloman shared them with Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller as they were assembling their 2021 documentary Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song.

Given the blessing to make the film by Cohen himself before his 80th birthday, Geller and Goldfine took their cue from Alan Light, who wrote the 2012 book The Holy Or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley, and the Unlikely Ascent of “Hallelujah,”a book that Cohen praised and even once endorsed on stage. The filmmakers approached the film from the perspective of the song and, like Light, simply asked for Cohen’s blessing to do so.

“It was really just this tacit blessing saying, ‘Don’t block this from happening,’ and that was it,” says Geller. “There was never a response from Leonard and there was never any string attached saying, ‘You can’t touch on this subject, or that subject,’ either. It was very much hands-off.”

Goldfine and Geller began collecting research, eventually documenting transformative moments in Cohen’s life and career, from transitioning from poet to singer-songwriter in the 1960s, earlier rejection by labels, and a five-year sojourn to a Zen Buddhist colony in 1994, to the embezzlement of millions of dollars from a then-71-year-old Cohen by former manager Kelley Lynch (who also sold many of his publishing rights) and through his momentous final Old Ideas World Tour, all told through the prism of his iconic 1984 song “Hallelujah.”

Weaving in archival recorded interviews as well as some newer ones with Cohen, including excerpts from dinner conversations with Sloman, Hallelujah is rounded out by stories and reminisces from longtime collaborator Sharon Robinson as well as John Lissauer, who produced Cohen’s seventh album Various Positions and arranged the first-ever recording of “Hallelujah.”

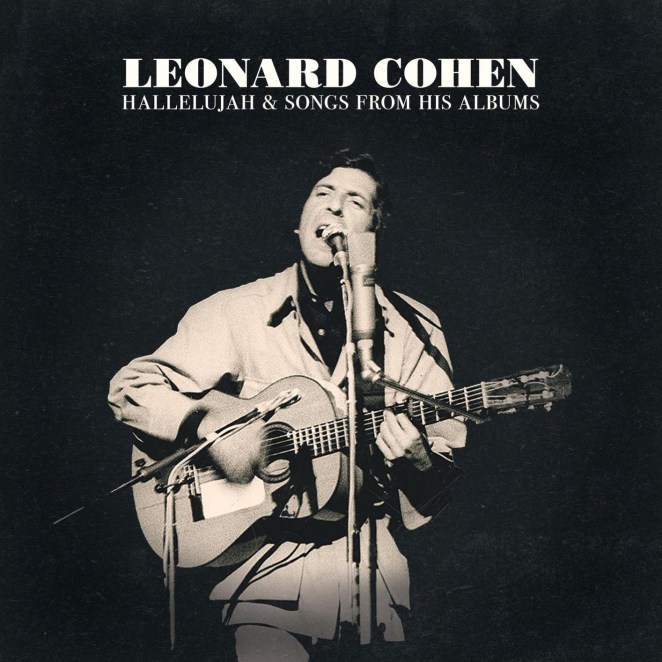

Accompanying the documentary is the anthology, Leonard Cohen: Hallelujah & Songs from His Albums, featuring 17 tracks from Cohen’s career, including a previously unreleased live performance of “Hallelujah” from the 2008 Glastonbury Festival.

Those who have covered the song, including Rufus Wainwright, Eric Church, Amanda Palmer, and Regina Spektor also appear in the film. Cohen’s longtime friend Judy Collins, who released her cover of “Suzanne,” which boosted her fifth album, In My Life, in 1966, remembered a greener Cohen, who lacked confidence in his music and suffered severe performance anxiety in his earlier days.

“Leonard came to me in 1966 and said, ‘I can’t sing and I can’t play a guitar,’ and then he played this song to me,” says Collins in the film, turning to play “Suzanne” on the piano. “And then he sang me ‘Suzanne.’ After he finished I said, ‘Well that is a song and I’m recording it tomorrow.’”

A year later, Collins—who also covered Cohen’s “Sisters of Mercy,” “Joan of Arc,” “Priests, “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye,” “Famous Blue Raincoat,” “Story of Isaac,” “Take This Longing,” “Dress Rehearsal Rag,” and “Bird on the Wire” throughout her career—invited Cohen to play an anti-Vietnam War fundraising concert at Town Hall in New York City and instigated his first-ever performance on stage. “I said you can’t hide in the shadows anymore,” Collins told Cohen. “You have to come sing in public.”

His guitar out of tune and overcome with nerves, Cohen, his voice cracking, sang several lines of “Suzanne” before walking off the stage. Collins comforted Cohen backstage and went back out with him to finish the song. “The audience was generous,” Cohen can be heard saying in the film. “It was just nerves.”

Around the time Cohen began working on his sixth album, Recent Songs, in 1979, he connected with Robinson, who would end up touring with Cohen through 1980. They collaborated on several projects throughout the next few decades, including co-writing his 1988 I’m Your Man track “Everybody Knows” as well as “Waiting for the Miracle,” off his ninth album, The Future, in 1992. The pair co-wrote, produced, and arranged Cohen’s 2001 album, Ten New Songs, and would tour together again from 2008 through his final tour ending in 2013.

“Working with him definitely changed my approach to writing songs,” shares Robinson, who has also written songs for Diana Ross, Roberta Flack, Aaron Neville, Don Henley, Michael Bolton, and others. “When I used to write for Geffen [Records] and Universal, it was more writing for the commercial market, where you were sort of trying to combine your own personal experiences into a form that was relatable to many people, but after working with Leonard, my writing had become much more personal and, hopefully, more poetic. It’s harder, but having worked with him, it was just so special and a unique privilege of an experience.”

Words were always of the utmost importance to Cohen, says Robinson, who says he often labored over songs, taking five years and dozens of drafts to complete “Hallelujah.” “His poetry and his lyrics were probably the first thing that he focused on, always,” adds Robinson. “Obviously he came from the world of poetry, so he was finding these human experiences and these human condition-type ideas and finding a way to express them that was deeper than how we might think about them on a day-to-day basis.”

Cohen “turned over every leaf,” according to Robinson, referencing his 1988 song “Take This Waltz,” which was inspired by the poem “Little Viennese Waltz” by Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, and the line In a cave at the tip of the lily.

“Most of us, if we look at a lily, we are aware of that cave but we don’t really think about it, but for him to use that as part of a way of expressing something about human life, it’s just brilliant,” says Robinson. “He took a lot of time with his writing, and he never settled for anything. He was never happy with a lyric and he kept changing it, and sometimes we shelved it and moved on.”

Sloman was instantly fascinated by Cohen’s words and music from the moment he saw the 1971 Robert Altman Western film McCabe and Mrs. Miller, which featured several songs from his 1967 debut Songs of Leonard Cohen. “I was really drawn, initially, to his work before I got the assignment from Rolling Stone magazine to cover that tour,” remembers Sloman, who was assigned to cover Cohen’s tour around the 1974 release of his fourth album, New Skin for the Old Ceremony, including six shows at The Bottom Line in New York City.

“I was already familiar with ‘Suzanne,’ but it wasn’t until a few years later when I saw the Altman film McCabe and Mrs. Miller that I was struck by ‘The Stranger Song,’ ‘Sisters of Mercy,’ ‘Winter Lady,’’’ adds Sloman. “I was just astonished how great those songs were, and to me, they made the movie, so I immediately rushed out and bought the first three [Cohen] albums, and I was hooked. Of course, I was excited to get the plum assignment of trailing Leonard around.”

Geller and Goldfine were enamored from the first time they saw Cohen perform at the Paramount Theatre in Oakland during his final tour. ‘Those were mind-boggling shows,” says Geller. “It really was like no other concert I’ve ever been to and I equate it to Leonard’s own words. He would say to the audience, ‘It’s great to gather here together.’ ‘Gather here together’ means both the performer and the band and the audience, and it’s a very different way of saying, ‘Thank you for coming to my concert.’ Gathering really felt like a great way to describe what was happening at those concerts.”

Seeing Cohen was more of a spiritual experience, according to Goldfine, particularly during those final years. “People describe going to a Leonard show, especially in that last five-and-a-half-year period, they all talk about the spiritual aspect of a Leonard Cohen concert, and I think that it was universal. Everyone that went to a concert with Leonard no matter where they took it in, had a spiritual experience.”

There’s no doubt if Cohen were still alive, he would still be writing and working until the end, says Robinson, which he ultimately did prior to his death on November 7, 2016, at the age of 82. That year, Cohen offered his final assemblage, a collection of placid and humorous hymns around his own mortality on his 14th album, You Want It Darker, which he released just 17 days before his death.

“When we were touring in this last go-round, 2008 to 2013, he would always say that he just wanted to keep going until he dropped,” shares Robinson. “He always believed that the artist’s cachet was within the realm of new music, so he was always interested in creating new music, which he did, and he put out a lot of new work, as much as he could get done, right until the end of his life.”

Photo courtesy Sony Picture Classics