This is Part II of this story. Part I can be found here.

Videos by American Songwriter

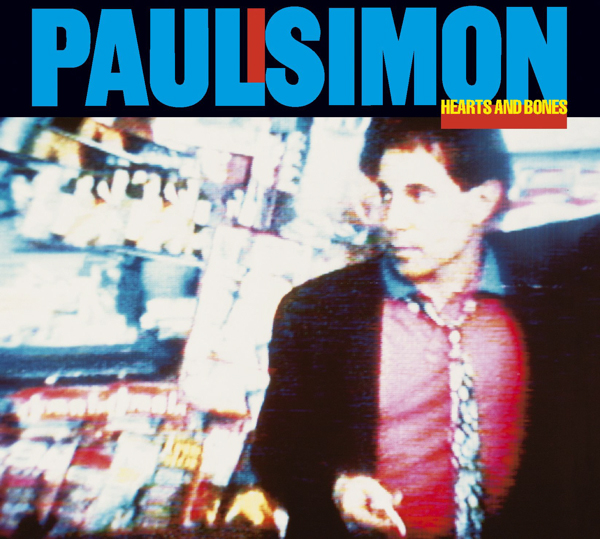

Paul Simon’s Hearts and Bones was as momentous in my life as was Simon & Garfunkel’s Bridge Over Troubled Water in 1970. Which, in the context of how I saw the world then, had an impact on me which was profound and transformative. Both albums brought home a truth I already understood, but was articulated so clearly: That very few things humans can do will ever measure up to the power of an album like this, and the force of these songs that seemed to do everything and more songs can do. The power of song is unlike other forces in our lives. It speaks to our hearts and our minds at the same time, comforts, engages and inspires us, and makes the world more bearable, and our lives less lonely, with music of the ages.

Hearts and Bones arrived as a masterpiece then, and its greatness has not worn off. When it came out it brought meaning, and romance and love and poetry, to my life when I needed it the most. I was on my own during the first years after college. I was single and in the midst of romantic turmoil. That title song spoke to me in a way few songs ever had, before or since. It did that thing that music can do – it attached itself to emotional moments of my life so deeply that the attachment never faded. It always brings me back to that moment. It’s the magic of song.

Yet it was more than that, as Simon always was a lifelong songwriting hero, whose every album changed my life when they arrived. For many of us, he was our teacher – showing us how to do it, teaching us new chords, ways of using lyrics, courage to use content rarely used in song, and remarkable production and sonics.

His genius with the “crucial balance,” as he called it, of both the words and music, always has astounded and inspired me, as it has millions, enriching our lives with such fully realized artistic songs. His voice on that album or any album always had the real effect of an old friend singing directly to my soul. Because we had been cheered by that voice for years. He was an old friend.

So there are endless personal reasons to be offered which explain my love for this album. And decades later, its magic has not worn off. It is a masterpiece, both in terms of songwriting, and also of record-making.

Simon told me and others in interviews that he felt he’d failed on Hearts and Bones – not the songwriting, the production. That he’d written good songs but made bad records out of them. This was not an estimation shared by many of his fans I knew who loved this album. Never did the production seem to me to be lacking, quite the opposite.

Nor did he produce the album alone; it was produced by Roy Halee, Lenny Waronker and Russ Titelman with Paul -and these three are no slouches. Nor did he promote the album, and the promotion is directly attached to an album’s emergence. All of which points to the truth of being a songwriter-singer-recording artist at his level. Regardless of those other contributions, Paul knew that to his audience, it was all about him. Those songs began and ended with Paul.

That estimation of the album and his responsibility for it led him to Graceland.

Certain, as he said, that “nobody was listening,” he went to Africa on a musical expedition with Roy Halee, which became Graceland. From then on, he decided, he would make the track first, and write the song to the track, ensuring the record would sound good by making the record first, before writing the song.

When I learned of this method, growing up as did so many songwriters with great reverence for his songwriting, which he did with voice and guitar, it seemed daunting. How one goes about creating a track before knowing the song, and then has to write a song to fit, was tough to conceive then. When discussing it in an interview, I said that it seemed like a really hard way of writing a song.

“It is,” Simon agreed. “But, you know, there is no easy way.”

Of course, he is right. And now this method of writing a song to a track is prevalent, and exactly as he said, no harder than more traditional methods. In fact, as Simon came to discover, and which I’ve also come to understand, a great track can lead to an exultant, unexpected song.

So Hearts and Bones was the last chapter in his life-story of Simon writing the way he always wrote – with voice and guitar – for a long time. And let’s face it – few people in history have done more with voice and a guitar than this guy. That’s where “Bridge Over Troubled Water” was born, after all. (On recent albums, he has written a few songs by the old method, voice and guitar, and they are wonderful, such as “Love In Hard Times” and “Questions for the Angels.”)

All these years later, Simon’s judgment of the production on Hearts and Bones is too harsh and not accurate. Its production is inventive, inspired, and intimate. The tender rhythmic beds of percussion hint at the polyrhythms to come, but are wed delicately here with warm textures of guitars, melodic bass, vocal harmonies, and rich keyboard parts, creating a sound that is deeply heartfelt and unique.

Of all the serious songwriters, he’s can be quite funny, even in songs. To explore his own self-obsessed tendency to think too much, he wrote here not one but two songs with the same title, “Think Too Much.” Who does that? Simon did, and it’s wondrous:

The first song is breezy and lightweight. But the sequel (“Think Too Much, B.”) is profound, and haunting. Musically it’s elemental, revolving around only two chords, A major and F# minor (aka the I and the VI), two sides of the same coin, with a poignant and passionate melody locked in with the groove. It’s a seed of Graceland, the soulful rhythm inspiring the discovery of words both funny and serious.

Like scenes in a movie, we cut to the final verse, his father on his death bed, informing Paul that no amount of worry – of thinking too much – will help. “He said there’s not much more that you can do/go on and get some rest/and yeah, maybe I think too much.” It’s the resignation of the ages, the sober understanding that reality persists, despite all the worry in the world. Yet it’s linked so organically to the music that the answer is evident: beyond thinking, beyond intellect, is the source. The music.

“Rene and Georgette Magritte (With Their Dog after the War)” is more remarkable and essential Simon, another depiction of an artist in the world, weaving together a dimensional portrait of the surrealist in New York with a stunning, complex melody.

He transformed the unwieldy title into a single melodic phrase of organic grace. Around that core, he allowed the story to unfold, sparked by a measure of mystery: Magritte’s secret passion for great doo-wop groups of the ’50s with a mesmeric recitation of their arcane names (“The Penguins, the Moonglows, The Orioles, the Five Satins…”), enriched by the deep resonance of the voices of the actual Harptones singing. It’s the height of the art: brilliant songwriting, ingenious production and passionate performance all combined.

He told me that he felt none of his songs were perfect, but some closer than others. I brought up “Hearts and Bones.” He thought for a moment, and said, “Yeah. It’s close.”

It starts with a gentle but intoxicating percussion groove provided by the great Airto Moreira locked to Paul’s ascending acoustic guitar riff in E major, the essential guitar key. This is Paul in his element. The lyric starts like an old joke: “One and one-half Wandering Jews free to wander wherever they choose…,” a reference to his brief marriage to Carrie Fisher. But levity, again, is a bridge he builds to deeper stuff. Time becomes disjointed, like in memories or dreams, and a cinematic montage of a marriage and its moments proceeds.

At the end the very guy who told us we were all slip-sliding away, gives us his rawest and most human expression of love lasting :

“You take two bodies and you twirl them into one

Their hearts and their bones

And they won’t come undone

Hearts and bones…”

The musicianship throughout is impeccable, played by three greats who are already gone, Jeff Porcaro, Richard Tee, and Eric Gale. The great Steve Gadd, who Simon called “the great drummer of his generation,” is also here.

Great musical moments abound: Al DiMeola’s astoundingly fast, furious but fluid guitar solo on “Allergies,” Phillip Glass’s plaintive orchestral coda to “The Late Great Johnny Ace,” Airto Moreira’s percussion throughout, and Simon’s own exquisite acoustic guitar work.

We also have here one of Simon’s most beautiful and affirmative songs, “Train In The Distance.” Wrapped around an evocation of the classic “Mystery Train,” Simon’s own mystery train is unseen; it’s a sound – far off in the distance – that unites us like our ancestors around a fire, or kids around radios and record players.

“Everybody loves the sound of a train in the distance,” he sings, and then, in a rare instance of the songwriter stepping outside of his song to comment on it, he wraps up this song and the entire collection with this understanding: “the thought that life could be better is woven indelibly into our hearts and our brains.”

That in this life we humans get our hearts and our bones consistently trampled. Yet hope remains, and it’s hope we get from music like this, music which still makes us smile and think and sing along , even after all these years. Hearts and Bones stands along with all his other albums solo and with Garfunkel, forever powerful and beloved.

When asked which albums I would nominate for inclusion, I immediately thought of my two favorites, each of which I cherished but which never got much acclaim. The first I considered was Mingus, an absolute masterpiece of songwriting, musicianship and recording which few – even her own fans – embraced. Gary seemed to agree with their lack of love for it.

This album, Hearts and Bones by Paul Simon, was my second idea. It’s one that, over the years, has seemed to garner much more awareness and even love, especially among songwriters and Paul Simon fans. It certainly had a place and deep moment in my life.

But in Simon’s career, especially compared to the immense success of certain albums, including those he made as part of Simon & Garfunkel, its reception was underwhelming to a heartbreaking extent to Simon. That perceived failure – which he took on himself -is what led him to his next album, Graceland, which he built on musical tracks he made in Africa with musicians there. He did that not out of any thoughts it would be a commercially successful album, though it was. He did it, he said, because he felt “nobody is listening.”

He told me that it sold a million copies. Yet compared to the twenty million copies of Bridge, Simon said, “that means nineteen million people chose not to buy it.” Which seemed like an awfully detrimental way of looking at it, as was his assumption that it was his failure which caused this, by not making a good enough album.

Of course, we know there are many reasons people don’t buy albums even by by artists they love, which often has to do more with awareness. Perhaps it was not promoted the way previous albums were, so that his fans didn’t know about it. The idea that they all were aware of it, yet decided against buying it is unlikely.

It came out in the context of the early eighties, when music was all about the music of Madonna, Michael Jackson and Prince. All of whom were born the same year (1958). Simon came from an earlier time, though not that much earlier. Many have suggested that the focus on these artists and their peers got in the way of Hearts and Bones receiving deserved attention from the press and the public.

What is undeniable is the ongoing and expanding appreciation for this landmark album by his fans and the world at large. Some of the songs from Hearts and Bones have become among his most famous, such as “Magritte,” which the artist has performed often in concert.

The original title of the album was Think Too Much, connected to the two songs Simon wrote with the same title, the only time he’s done that before (of which we know). It was Mo Ostin, CEO of Warners, which was Paul’s label at the time, who convinced Simon to title the album Hearts and Bones.

Which brings us back to the question which lies beneath this journey through this beautiful album. Despite all these words here, is this an album worth listening to?

Yes.